Inclusive development, translation, and

Indigenous-language pop: Yoku Walis’s Seejiq hip hop

Darryl Cameron Sterk

Department of Translation, Lingnan University, Hong Kong

shidailun@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0232-0855

Abstract

This article is about a cost-effective approach to inclusive development in a settler state that shows what translation has to offer minorities. For almost two decades, Taiwan’s government has rewarded Indigenous minority recording artists who sing in endangered ancestral languages at the Golden Melody Awards (GMAs), Taiwan’s Grammys. These language-based GMAs stimulate the private production of popular music in such languages. They also stimulate translation into such languages, which certain recording artists have been learning as adults. I found that one GMA hopeful, Yoku Walis, translated her hip-hop lyrics from Mandarin Chinese into Seejiq, her ancestral language, with a language learner in mind, and that a pedagogical goal also guided the titling of her music videos. But language pedagogy is only one part of an innovative package. Yoku’s Seejiq hip hop is a contribution to inclusive linguistic and cultural development. The language-based GMAs illustrate the ways in which settler states such as Taiwan can help to empower Indigenous translators such as Yoku to make such contributions.

Keywords

Indigenous policy, language revitalization, minority translation, popular music, Taiwan, Seejiq

1. Introduction

For almost two decades, Taiwan’s government has rewarded Indigenous recording artists who sing in endangered ancestral minority languages at the Golden Melody Awards (GMAs), a Taiwanese analogue to the Grammys. These awards stimulate the private production of popular music in such languages. They also stimulate translation into such languages; Indigenous-language GMA hopefuls write lyrics in Mandarin Chinese and translate them into ancestral languages that they are learning as adults with the assistance of fluent speakers, usually elders.

In this article, I situate these awards in the context of a redefinition of inclusive development in settler states such as Taiwan over the past half-century. Having tried to include Indigenous minority peoples in development by assimilating them, such states are now trying to empower them to develop their ancestral languages and cultures in multicultural and multilingual frameworks.

I argue that of all the approaches to inclusive development a settler state can adopt, language-based popular music awards are particularly cost-effective. The cost-effectiveness of inclusive development approaches has been assessed in the context of “minority language policies” (Grin & Vaillancourt, 1999). Minority language music programming has been researched (Grin & Vaillancourt, 1999, p. 31), but not popular music awards such as the language-based GMAs. For a minimal cost, these awards raise the profiles not only of individual recording artists but also of their languages through the creation of “space for the use of these languages in public and prestigious settings” (Shulist, 2018, p. 523). Shulist (2018) emphasizes the efforts of grassroots actors in the creation of such space, but I believe that settler states also have a role to play. Shulist considers the creation of such space as a factor that contributes to language revitalization, but I regard revitalization as a form of development, because every language learner has the potential to innovate, to make a language new.

In Taiwan, Indigenous-language recording artists are language learners who address linguistically and culturally innovative songs to fans who are potential language learners. As a scholar of K-pop (Korean popular music) has commented, “[M]any students want to learn Korean because they like K-pop” (Jung, 2021, p. 1). The comment should apply equally well to I-pop (Indigenous-language popular music). Translated I-pop (that is, pop songs, the lyrics of which have been translated into Indigenous languages) is material for what O’Connell (2011) has termed “casual language learning”, which complements formal language learning. For learners of endangered Indigenous languages, who are typically beginners, translated I-pop is easy to understand because the translators, who may be language learners themselves, translate as simply and as straightforwardly as possible.

To support this argument, I have undertaken a case study of a recording artist named Yoku Walis (given name, patronym), who is learning her ancestral tongue, the Truku dialect of the Indigenous language Seejiq (pronounced [se'ed͡ʒɪq] or [sə'd͡ʒɪq]), which is also known as Seediq ([se'edɪq]). Seejiq is spoken by a few thousand people around the geographical centre of the main island of Taiwan. Most speakers are over the age of 50; Seejiq is literally a grandmother tongue. But young people like Yoku, who is in her late twenties, have been learning it as adults. One approach to language learning that Yoku has adopted is to translate her Mandarin-language hip-hop lyrics into Seejiq with the help of a peer named Walic Huwac and an elder named Lituk Teymu. In fact, Yoku has released an album of Seejiq hip hop.

Yoku is hardly a household name, so I should explain why I have chosen her for my case study over more famous local Indigenous singers such as Kulilay Amit (a.k.a. A-mei) or Matzka, Suming Rupi or Aljenljeng Tjaluvie. Kulilay Amit is the most famous Indigenous diva, but she does not sing in her ancestral language, and neither does Matzka in his ancestral language. Suming Rupi and Aljenljeng Tjaluvie sing in their ancestral languages, but I do not understand these languages. I do have reading knowledge of Yoku’s ancestral language, Seejiq, so I have been able to analyse the translation of her lyrics from Mandarin into Seejiq. I know Yoku, too, and was able to interview her on Zoom on 23 December 2020 and send her follow-up questions using Facebook Messenger. I also know Walis Huwac and Lituk Teymu, and was able to interview them separately on social media. Finally, Gideon Su, the producer of Yoku’s album, wrote a master’s thesis (Su, 2020) about its production, which has enabled me to triangulate and supplement information from the interviews.

2. Theoretical background

Any case study of inclusive development in a settler state should include an acknowledgement that “development” may still have a negative valence for many Indigenous people. “Tribal, aboriginal, or First Nations societies had long been destined”, it was once assumed, “to disappear in the progressive violence of Western civilization and economic development” (Clifford, 2013, p. 7). When such peoples did not disappear, they were left “at the mercy of predatory national and transnational agents of ‘development’” (p. 17). Clifford (2013), however, also writes of “strategies of survival and ‘development’, individual and communitarian, that are pursued to significant degrees on Native terms” (p. 81). Translation appears to be a strategy of Native self-development throughout Clifford’s book, and an expression of “indigenous agency” (p. 8).

The role that an Indigenous translator can play in development had been a theme in Translation Studies for almost two decades before Clifford (2013) proposed “translation” as a “theory/metaphor” that “keeps us focused on cultural truths that are continuously ‘carried across,’ transformed and reinvented in practice” (p. 48). In his seminal article on the translation of minority languages, Toury (1985) asserted that “translating has actually contributed to the development of these languages and their cultures” (p. 3). Recently, Kuusi and his colleagues have been highlighting translation’s role in minority language revitalization (Kuusi et al., 2017). They refer to translation’s “ambiguous potential for the development of minority languages” (p. 148), an issue I shall return to in the conclusion.

Here in the introduction, I should like to situate my study by comparing it to Koskinen and Kuusi’s (2017) “Translator Training for Language Activists: Agency and Empowerment of Minority Language Translators” in terms of what Marais (2018) calls “a complexity approach that accommodates both structure and agency” (p. 97) in his essay on “translation and development”. Like Koskinen and Kuusi, I am interested in the agency of minority language translators and their empowerment to pursue self-development, even though the structural means of empowerment is different in each case. For Koskinen and Kuusi it is a translator training programme, whereas for me it is a policy of cultivating and rewarding Indigenous musical talent that indirectly stimulates translation. It has to be kept in mind that any social structure is composed of agents who, in turn, constitute the structure, and that a focus on a certain programme or policy may leave other aspects of structure in the shadows, particularly in a short article.

The expression of agency I focus on in this article is the translation of popular music lyrics into endangered Indigenous minority languages. In adopting this focus, I am trying to begin to fill a gap in knowledge that spans translation studies and ethnomusicology. In translation studies, Sturge (2007, pp. 115–116, 122–127) discusses the translation of “traditional” song lyrics out of Indigenous languages, but not of “modern” pop lyrics into such languages. Susam-Saraeva (2019) identifies domestication as a way to appeal to local audiences in the translation of “interlingual cover versions” of “popular songs”. Finally, Taviano (2016) approaches the translation of the genre of hip hop around the world as a form of “resistance”. But none of these studies sheds light on the translation of pop music lyrics into endangered Indigenous languages by language learners for the benefit of fans who are potential language learners.

Ethnomusicologists have studied the production of I-pop, including hip hop, as a form of “resistance” to problematic government policies or language ideologies (Del Hierro, 2016; Faudree, 2013; Mitchell, 2000; Tucker, 2019). Indigenous-language hip hop has also been studied in the context of language revitalization (Barrett, 2016; Przybylski, 2018). Two ethnomusicologists, Faudree (2013) and Przybylski (2018), have reported on cases of translated I-pop as I have defined it. Surely the translation strategies that the Indigenous recording artists adopted would be relevant to resistance and language revitalization? However, the ethnomusicologists did not study them. How have popular music lyrics, in particular hip hop, been translated from settler majority languages into endangered Indigenous minority languages, and why? This is the question I have tried to begin answering with a case study of Yoku Walis’s Seejiq hip hop.

As is the case with any study, mine has limitations. To prove the cost-effectiveness of language-based popular music awards as an approach to inclusive development in a settler state, I should undertake a comparative study that investigates the consumption and not only the production of translated I-pop. I outline possible follow-up research directions in the conclusion. In the next section, I sketch the historical background to Seejiq hip hop.

3. Inclusive development and Indigenous policy in Taiwan

The Seejiq specifically, and Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples in general, are Austronesian. According to the out-of-Taiwan hypothesis, the ancestors of Austronesian peoples such as the Malagasy and the Maōri set out from Taiwan over four thousand years ago. During the subsequent millennia, they settled on islands as far afield as Madagascar and New Zealand. Over the past few centuries, Austronesian islands have been subject to new waves of settlement. From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, for example, Taiwan’s western plains were settled by Chinese farmers, who deterritorialized Austronesian communities, pushing them into the mountains, where they lived “beyond the pale”. It was not until over a decade into the Japanese era (1895–1945) that Seejiq communities in the central mountains submitted to the authorities.

In 1945, Taiwan came under the control of the Republic of China (ROC). At the time, the ROC was a dictatorship dominated by the Kuomintang (KMT), the Chinese Nationalist Party, under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek. After Chiang lost the Chinese Civil War, the nationalists retreated to Taiwan and imposed martial law and a monolingual national language policy on a polyglot population. Mandarin Chinese, the “national language”, was taught in schools, while ancestral languages such as Seejiq were suppressed. The party-state might have claimed that it was attempting to include Austronesian peoples in development, but development was not “on Native terms” (Clifford, 2013, p. 81). From a Native perspective, the national language policy was an attempted “linguicide” (Zuckermann, 2020, pp. 189–190). Unlike in other Asia-Pacific countries, where the church suppressed Native languages, the church in Taiwan helped to develop such languages by translating the Bible into them and using them in Sunday services (De Busser, 2019). But, like the state, the church suppressed Native cultures. By the 1980s, Native children were shifting away from their ancestral tongues to Mandarin and from “traditional” to “modern” modes of life. This was the context for the founding of the local Indigenous movement.

Without intending any value judgement, I distinguish “radical” and “reformer” wings in the Indigenous movement. Radicals have demanded the restoration of Indigenous sovereignty, whereas reformers have sought the recognition of Indigenous status (Simon, 2020). The reformers won recognition in the mid-1990s, when the KMT was attempting to pivot towards democracy. Taiwan’s Austronesian people were constitutionally recognized as 原住民 Yuánzhùmín, or “Indigenous”, in 1994, and as linguistically and culturally defined 原住民族 Yuánzhùmínzú, or “Indigenous tribes”, in 1997. At that time, the Seejiq were classified together with another tribe, the Atayal, but in 2008 they were recognized as being distinct. To the radicals, recognition deflects attention from the real issue – sovereignty – whereas to the reformers, multicultural and multilingual democracy since the 1990s is an improvement over the authoritarianism under martial law from 1949 to 1987. Having achieved recognition, reformers have persuaded the state to support linguistic and cultural revitalization.

During the past three decades, the state has paid more than lip service to the Indigenous policy. Investments have been made in “Indigenous language education” (McNaught, 2021) in an attempt to undo some of the damage inflicted under martial law. Translators have played important roles in language education by compiling bilingual language-learning materials, including textbooks and online dictionaries. More recently, the emphasis has shifted from language education to language development. Promulgated in 2017, the Indigenous Languages Development Act provided for an Indigenous Languages Research and Development Foundation and a network of language development offices around the country. The Seejiq Language Development Office is located in the central Taiwanese town of Puli. Translation, including that of Seejiq hip hop, is an important activity at the office.

As I was revising this article in May 2022, a petition was filed protesting another policy, Bilingual 2030, for deprioritizing the development of Taiwan’s ancestral languages (Everington, 2022). I am not debating the balance that Taiwan should strike between foreign-language and ancestral-language development; I am simply pointing out that when resources are limited, as they always are, they should be used wisely. I discuss a particularly cost-effective approach to the development of Indigenous languages, and the corresponding cultures, in the next section.

4. The invisibility of translation at the Golden Melody Awards

Indigenous singers have released dozens of ancestral-language albums, each a drop in a global ocean of pop, over the past two decades in Taiwan. The singer who has received the most popular and scholarly attention is Suming Rupi, who speaks Mandarin and often sings in the Amis language. Scholars have discussed Suming’s “language activis[m]” (Hatfield, 2021, p. 35), his “cyberactivism” (Tan, 2017, p. 41) and his “alternative cultural activism” (Tsai, 2010). Tsai (2010) notes that “Suming’s hope is that by making Amis culture fashionable, young Amis would be drawn back to their own culture, and take up learning the language and traditions”. But the translation of his lyrics from Mandarin to Amis has not been discussed. In fact, the translation of pop music lyrics into Indigenous languages has, in general, been invisible (cf. Venuti, 1995). The fact that the lyrics are in Indigenous languages has, however, attracted some attention, not all of it positive.

At the Golden Melody Awards (GMAs) in 2000, an Indigenous recording artist named Paudull won the male Mandarin singer award for a mainly Mandarin song entitled “海洋” Hăiyáng, “Ocean”. Chen (2007) points to Paudull’s use of prosodic vocables such as hi-yan, which sounds like the Mandarin word for “ocean”, in the chorus. Such vocables feature in many Indigenous musical traditions in Taiwan, including among the Puyuma, Paudull’s tribe. Chen informed me (by e-mail on 11 September 2021) that Paudull’s win provoked “complaints from Taiwan’s record companies”, as if the Puyuma prosodic vocables should have rendered him ineligible for this award.

Paudull won another award at the GMAs that year for writing a song entitled “神話” Shénhuà, “Myth”. Sung by Paudull’s niece, Samingad, “Myth” was a milestone in the development of I-pop in Taiwan, because it was sung entirely in Puyuma. The lyrics, however, were originally in Mandarin; they were translated into Puyuma by Paudull’s father (Chen, 2007, p. 229). Born in 1967, Paudull may well have been capable of translating into Puyuma, but singers born in the 1970s and later have been increasingly likely to need assistance when they translate into their ancestral languages.

The GMAs in 2002 marked another I-pop milestone, when Biung, who is ethnically Bunun, was named best male “dialect” singer. The “dialect” awards had been introduced in 1991 as part of the KMT’s attempt to appeal to the majority of Taiwan’s voters, who were native speakers of Taiwanese, as Southern Hokkien is known in Taiwan. Linguistically, Taiwanese is a distinct language, not a dialect, but it was known as a “dialect” in those days. Now that Biung had won a dialect award for singing in Bunun, there was no award specifically for Taiwanese singers.

As a result, the male and female dialect singer awards were renamed the male and female Taiwanese singer awards in 2003, and two new language-based awards were introduced: one for another Sinitic language called Hakka, the other for Indigenous languages. There had been an album of the year award since 1990, but no language-based album awards. Four language-based album awards appeared in 2005: for Mandarin, Taiwanese, Hakka, and Indigenous languages. Ethnomusicologists have their theories about the motivation behind the introduction of these awards. Liu Chih-chun (by e-mail on 14 September 2021) took the positive view that the awards were introduced by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) administration of Chen Shui-bian, who won the presidency in 2000, in order to dismantle the language hierarchy in which Mandarin was valorized and Taiwanese vilified. Huang Kuo-chao (by Facebook Messenger on 10 September 2021) took a pragmatic view, namely, that the awards were attempts by President Chen to appeal to a broader electorate. Huang’s view is also plausible: the GMAs have been awarded by the government since their inception and therefore politics cannot be excluded from explanations of the way in which they have functioned. The political background is that whereas the KMT needed to appeal to native Taiwanese voters, whose ancestors had settled Taiwan before 1945, to survive in a democratic political system, the DPP needed to broaden its appeal beyond the native Taiwanese electorate. The language-based awards can plausibly be described as planks in DPP President Chen Shui-bian’s re-election platform in 2004.

Politics aside, the language-based GMAs are arguably cost-effective means of promoting Indigenous linguistic and cultural development. Current cash prizes are 100 thousand NTD for the Indigenous-language singer award, and 150 thousand NTD for the Indigenous-language album award (Bu, n.d.), a total of 250 thousand NTD or about eight thousand USD. This is a drop in the ocean compared to the budget for the development of Taiwan’s national languages, including Taiwanese, Hakka, and Indigenous languages. (Taiwan plans to spend NT$30 billion [about one billion USD] to promote national languages, 2022.) As for their effectiveness, the televised broadcast of the GMAs has been watched by more than three million people in recent years (e.g., 32nd GMA Viewership, 2021). It is therefore a high-profile stage for Indigenous singers to perform on. It is hard to tell whether appearing on this stage in 2011 and 2016 has helped Suming make Amis culture “fashionable” (Tsai, 2010). But free, public data from the past few years suggest that recording artists like Suming do receive a “GMA boost” analogous to the “Grammy boost”. For instance, Aljenljeng Tjaluvie, who has won the Indigenous album of the year award twice, in 2017 and 2020, and also song of the year in 2020, enjoyed a spike in YouTube subscribers and video views in the week of the 2020 GMAs, according to Social Blade, a digital analytics website. Her Paiwan-language gospel pop hit “Thank You” (Tjaluvie, 2019), a paean to nurses during the pandemic, now has more than 2.5 million views.

Does this viewership figure index language development? Tjaluvie has published an online series of ten language-learning videos, including one for “Thank You” (Tjaluvie, 2020). This video has been viewed approximately three thousand times, but there is no indication in the comments of how much language learning it has inspired.

In this section, I have tried to render more visible the translation of popular music lyrics into Indigenous languages, but I did not discuss the translation process. I turn to that task now.

5. Yoku Walis’s Seejiq hip hop

Yoku Walis intended to be a nurse until she attended a singing competition at her alma mater that was judged by Aljenljeng Tjaluvie in the early 2010s. At the time, Tjaluvie, who is ethnically Paiwan, was known as a singer of Mandopop – Mandarin-language popular music. An alumna of the same nursing college, Tjaluvie saw (and heard) potential in Yoku and introduced her to the manager of a K-pop-style girl group, that is, a group of girls who sing in Mandarin while emulating the dance and musical styles of K-pop groups. Yoku spent five years singing and dancing in this group. Meanwhile, Tjaluvie released Vavajan, which won the Indigenous-language album award at the GMAs in 2017. Tjaluvie was now more famous for her P-pop (Paiwan-language popular music) than she had ever been for Mandopop. Tjaluvie’s success encouraged Yoku to consider singing in Seejiq: rebranding herself as a Seejiq singer might open a path to solo popularity.

In 2018, Tjaluvie invited Yoku to participate in a programme called Pasiwali that was sponsored by the Council of Indigenous Peoples (CIP) to develop Indigenous music talent. Tjaluvie was one of the mentors. Participants such as Yoku were coached in songwriting and in MV (music video) production. Like the translator training programme discussed by Koskinen and Kuusi (2017), this CIP-sponsored training programme was empowering; it provided Yoku with an opportunity she might not otherwise have had: she had the chance to write a bilingual song with an MV (Walis, 2019a).

The song has a pair of titles. The Mandarin title is “嬉鬧” Xīnào, “Fooling Around”. The Seejiq title is “Sinou”, which is typically spelled sinaw; originally “millet wine”, sinaw has come to mean “alcoholic beverage”. The two titles are related by metonymy; fooling around is something one might do when intoxicated. But Yoku does not explain the connection.

The song is mostly in Mandarin, but Yoku switches to Seejiq for the chorus, which, according to the hardcoded subtitles, ends as follows:

|

… SUPU |

=TA |

MIMAH |

SINOU |

|

… together.imp |

=1pl.nom |

af-drink |

wine |

|

… DRINK WINE WITH US |

|||

It is the kind of sentence that might appear in an elementary language primer, but as the subtitles for the chorus were not translated into Mandarin, no beginning learner of Seediq would be able to figure out what Yoku was singing.[1]

The song gave Yoku the chance to make an entire album in Seejiq, with a producer named Gideon Su, another of her mentors in the CIP-sponsored programme. After graduating from the Berklee College of Music in the early 2000s, Su (2020) had returned to Taiwan intending to produce “crossover” music. His most successful attempt to date has been “我身騎白馬” Goá Sin Khiâ Pe̍h-bé, “I Ride a White Horse”, a power ballad he co-wrote with the singer LaLa Hsu and which features a famous Taiwanese-language folk opera aria as the chorus of a Mandopop song. The song helped propel Hsu to five GMA nominations. Su notes two subsequent collaborations, with a Hakka band and with a Taiwanese singer, that resulted in six GMA nominations. Then, after asserting that the Indigenous-language GMAs launched the I-pop trend (p. 11), Su lists the winners of the Indigenous-language album award from 2005 to 2018 and analyses two of them, including Vavajan (pp. 16–17). I believe he was hoping finally to win a GMA with Yoku. Su’s attempt at musical crossover with Yoku involved a fusion of traditional instruments like drums (p. 43) and mouth harps (p. 58) and electronic music (p. iv). Figure 1 shows a parallel fusion of old and new in the cover art for Yoku’s album.

Figure 1

The cover of Yoku’s album, Vanished Valley.

On the right stands a traditional Seejiq singer named Ipay Sayun in front of a mountain; on the left is the modern Seejiq singer, Yoku Walis, in front of a warped tower. “The singer Yoku”, according to Su (2020), “is a young person who lives ‘transborder’ in the ethnic village and the city” (p. 23). Before elementary school, Yoku had lived with her maternal grandmother in the Seejiq village of Bwarung, but she grew up speaking Mandarin in the city of Taichung on the west coast. In recent years, she has been visiting Bwarung more frequently. She often stops at the Seejiq Language Development Office in Puli, a town along the way. There she translates her Mandarin-language lyrics into Seejiq with the assistance of her peer, Walis Huwac, and an elder, Lituk Teymu.

Walis Huwac grew up speaking Truku Seejiq in Bwarung with his grandparents and is now one of the very few young people – he is in his mid-twenties, a few years younger than Yoku – who can speak the language fluently. He is taking an experimental bilingual master’s programme in Seejiq culture at Providence University in Taichung City, which elementary school principal Lituk Teymu has been helping to run by liaising between master’s students such as Walis and the elders who teach Seejiq-language courses in traditional arts like singing and dancing, weaving and hunting in villages such as Bwarung. Yoku’s, Walis’s, and Lituk’s day trips to and from Puli are possible only because of National Freeway No. 6 from Puli to Taichung, which opened to traffic in 2009. Such are the contemporary conditions of mobility for Indigenous people in central Taiwan.

The first song of the album tells the “story” (Su, 2020, p. 24) of another kind of transborder journey. The story Yoku told was inspired by her Mandarin transliteration of her Seejiq name, 幽谷 yōugŭ. Yōugŭ means “remote valley”, the kind of valley premodern Seejiq people lived in – the kind of valley which is “remote” only from a contemporary urbanite’s perspective. The remote valley in the first song on the album (Walis, 2020), which is entitled “Mkuung Ayug”, is identified in Christian terms as “the valley of the shadow of death” from Psalm 23:4.

Yoku begins the song by reciting a Seejiq translation of Psalm 23:4:

|

Ana |

=ku |

m-ksa |

m-kuung |

ayug, |

|

although |

=1sg.nom |

af-walk |

af-dark |

valley |

|

Although I walk the dark valley, |

||||

|

ida |

=ku |

ini |

ki-isug |

ana |

manu … |

|

still |

=1sg.nom |

neg |

imp.fear |

no.matter |

what |

|

I still won’t fear anything … |

|||||

|

… kika |

kla-un |

=mi-su |

gaga |

su |

tuhuy |

knan. |

|

because |

know-pf |

=1sg.gen-2sg.nom |

aux |

2sg.nom |

accompany |

1sg.obj |

|

… because that you are with me is known by me. |

||||||

The object pronoun knan in the third line belongs to an old-fashioned, formal register now particularly associated with the Seejiq Bible. Yoku chants these lines as if she is in church. But then, although she continues to chant, she abandons the biblical register and rewrites the rest of the verse. Instead of taking comfort in the Lord’s rod and staff, she tries to open her heart. This is how she expressed her sentiment in Mandarin:

|

唯 |

有 |

心 |

打開 |

才 |

能 |

更 |

接近 |

彼此。 |

|

Wéi |

yŏu |

xīn |

dă-kāi |

cái |

néng |

gèng |

jiējìn |

bĭ-cĭ. |

|

only |

exist |

heart |

hit-open |

only |

aux |

more |

close |

this-that |

|

Only by opening our hearts can we get closer to one another. |

||||||||

Yoku translated this Mandarin line into two lines in Seejiq:

|

Ana |

=ku |

m-usa |

ana |

inu, |

asi |

ka |

rwah-an |

ka |

qsahur. |

|

even |

=1sg.nom |

af-go |

even |

where |

aux |

nom |

open-lf |

nom |

heart |

|

No matter where I go, it is a must that [my] heart be opened. |

|||||||||

|

Kika |

tduwa |

ms-dalih |

ita |

ka |

kana |

seejiq. |

|

thus |

try |

af.rec-near |

1pl.nom |

nom |

all |

person/people |

|

In this way we people try to come together with one another. |

||||||

In other words, Yoku fears no evil not only because the Lord is with her – or whoever the referent of the second-person singular nominative pronoun su in the Seejiq translation of the psalm may be – but also because she belongs to a coalescing community. And she expresses this sentiment in a vernacular, not a formal, idiom. It is as if we are witnessing the birth of popular music in the Seejiq language, which develops out of a biblical idiom but breaks away from it. The significance of the break is that whereas missionaries and their disciples developed Indigenous languages by translating the Bible (De Busser, 2019), now young Indigenous singers like Yoku are developing their languages and cultures by translating their lyrics. Yoku marks this break by switching from chanting to singing.

The rest of the song relates a vision of a rainbow reflected in an alpine lake. Since the release of the blockbuster film Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale (directed by Wei Te-sheng, 2011; see Sterk, 2020a), it has been common knowledge in Taiwan that the Rainbow is the bridge that worthy Seejiq people take to the afterlife. Traditionally, women showed their worth by weaving, men by headhunting, but today other kinds of contribution, including translation, are considered worthy.

An analysis of the translation of her vision of the Rainbow illustrates the approach to translation that Yoku took. In the original Mandarin, she exclaims:

|

在 |

這 |

篇 |

死寂 |

的 |

水裡 |

沉得 |

像 |

一 |

面 |

鏡子。 |

|

Zài |

zhè |

piān |

sĭ-jí |

de |

shŭi-lĭ |

chén-de |

xiàng |

yí |

miàn |

jìngzi. |

|

at |

this |

clf |

dead-still |

gen |

water-in |

sink-cmp |

like |

one |

clf |

mirror |

|

Sunken like a mirror in this expanse of deathly still water. |

||||||||||

I assume Yoku means that the sediment has “sunk”, meaning that it has settled, leaving the water clear; but then clear water would not form a mirror on a windy day. No clarification is offered in the choral antiphony, a heavily modulated line sung in Seejiq (see below) by three baritones, including Gideon Su, as if by the ancestors from beyond the grave:

|

打開 |

心思 |

|

Dă-kāi |

xīn-sī! |

|

hit-open |

mind-thought |

|

Open [your] mind! |

|

How does the singer open her mind?

|

當 |

我 |

撥開 |

它 |

看見 |

彩虹 |

的 |

倒影。 |

|

Dāng |

wŏ |

bō-kāi |

tā |

kànjiàn |

Căihóng |

de |

dào-yĭng |

|

when |

1sg |

stroke-away |

3sg |

see |

Rainbow |

gen |

reverse-image |

|

When I stroke it away, (I) see the reflection of the Rainbow. |

|||||||

Uncertain how the singer could stroke away her “mind”, the apparent antecedent of the Mandarin third-person singular pronoun tā, I raised the matter during my interview with Yoku. She explained that tā – “it” – represents all of the mental “obstructions” that have been blocking the singer. Only when she strokes it all away does she see the Rainbow in the mirror of the lake’s surface. The Seejiq translation, in contrast, is much more straightforward:

|

Ini |

qluli |

ka |

qsiya, |

saw |

bi |

gagi |

m-rdax. |

|

neg |

flow.af.imp |

nom |

water |

like |

true |

glass |

af-shine |

|

The water does not flow, how like a mirror it is. |

|||||||

|

Rwah-i |

lnglung-an! |

|

open-pf.imp |

think-lf |

|

Let [your] mind [literally, place of thought] be opened! |

|

|

Rwah-un |

=mu |

ka |

hiya, |

spaux |

sasaw |

Hakaw-Utux |

qta-an. |

|

open-pf |

=1sg.gen |

nom |

there |

collapsed |

shade |

bridge-spirit |

see-lf |

|

When that place (i.e., my mind) is opened by me, the reflection of the Rainbow is seen. |

|||||||

The Seejiq translation is easier to understand than the Mandarin original in three ways. First, it is because the water is not flowing in or out of the lake that it is like a mirror, without any mention of sinking. Second, whereas the original Mandarin switches from a verb meaning “open up” to one meaning “stroke away”, the Seejiq translation uses two forms of a verb meaning “open”: rwahi and rwahun. Third, rwahi and rwahun both focus the same subject, lnglungan, meaning “mind”, so the listener does not have to hunt for an antecedent.

Though straightforward, the translation is nonetheless lexically creative and lyrically effective. Literally collapsed shade, spaux sasaw is a translation of “reflection”. Gagi mrdax, literally a glass that shines, means “mirror”. The adjective-noun order of spaux sasaw may represent syntactic foreignization, but the noun-adjective order of gagi mrdax is definitely an instance of domestication. Regardless, both terms are innovations; they have, to my knowledge, only ever been recorded in the lyrics of Yoku’s song. Finally, these lines work lyrically in that qsiya rhymes with hiya, as does lnglungan with qtaan.

In the climax of the song, singer Yoku joins the community of worthy Seejiq people who are qualified to cross the Rainbow:

|

Seejiq |

=ta |

Balay |

ka |

ita, |

Balay |

wah! |

|

person/people |

=1pl.nom |

true/truly |

nom |

1pl. nom |

true/truly |

vcbl |

|

We are True People [i.e., the Seejiq], yes we are! |

||||||

Seejiq Balay is cognate with Seediq Bale, the subtitle of the blockbuster film I mentioned above. Seejiq Balay is the spelling and pronunciation in the Truku dialect, whereas Seediq Bale is in the Tgdaya dialect, which was chosen as the standard for the online dictionary of the Seejiq language of central Taiwan. The fact that Yoku is singing in Truku might be taken as evidence of her resistance to standardization (see Barrett, 2016), but the Seejiq people of central Taiwan have actually adopted three standards, one for each dialect. By translating her lyrics into standard Truku, Yoku has embraced the spirit of 3S3T, where 3S represents seejiq, seediq and sediq, the three pronunciations of the word for “person” in the 3Ts, the three standardized dialects, Truku, Tgdaya, and Toda (see Sterk, 2020b).

It is significant that Yoku separates Seejiq and Balay in the same quotation with the Seejiq first-person plural nominative pronoun ta, meaning that she includes herself in the community of the Seejiq Balay. Her Seejiq hip hop, a contribution to linguistic and cultural development, apparently qualifies her for membership. Ipay Sayun, the elder on the album cover, seems to welcome her into the community at 2:49 of the MV.

It is now clear that Yoku has been exploring a valley of life, not the valley of the shadow of death. The MV, however, crosscuts between the remote valley she has been exploring and a hotel room in the city in which she has been sleeping. Her exploration, it turns out, is a dream. As an urban aborigine who has embarked on a quest for her cultural roots, she may not know her culture very well – at least not yet.

Yoku explores her culture as it is lived in villages such as Bwarung in the rest of the album, particularly in the second song, “Jiyax Smipaq Babuy” or “Hog Butchering Day”. The song shows how the traditional and the modern combine in a wedding in a contemporary Seejiq village. Seejiq people may still slaughter pigs at their weddings, as they did traditionally, but they also drive “發財車” fācáichē, “get-rich vehicles”, meaning light trucks, like regular rural Taiwanese folks.

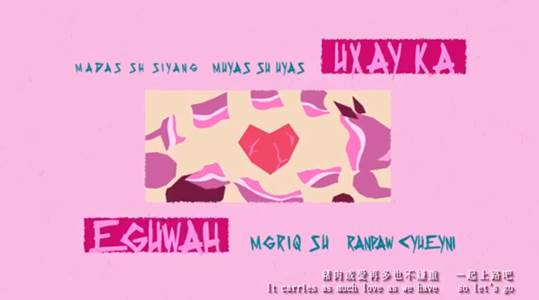

In the MV, the groom dresses up in traditional attire and rides in the back of such a truck on the way to a “remote” valley, where he will hunt a pig to slaughter at the wedding banquet. The groom also drives such a truck in the rap that follows the chorus, qualifying the song for “#rap嘻哈”, literally “hashtag rap hip hop”, on YouTube (Walis, 2019b). The Chinese characters “嘻哈” are pronounced xīhā in Mandarin and mean “hip hop”. Rap and hip hop are related in that the former is an element of the latter. Yoku wrote the rap in Mandarin and translated it into Seejiq. Another Seejiq singer, Lowking, performed it in a cameo. Figure 2 shows that the MV is animated, and that it employs creative titling.

Figure 2

Stills from the music video for “Jiyax Smipaq Babuy”

The first still features the bride and groom dancing around a cooking fire, while the second still illustrates the slaughtered babuy, with its heart at the centre. Both stills contain the same Seejiq translation of the right-justified subtitles in Mandarin (above) and English (below). In conjunction with the singing, these images form an audiovisual translational puzzle for the viewer to solve. In this way, the MV shows what audiovisual translation has to offer minority languages (O’Connell, 2011; cf. Taviano, 2016).

The English subtitles read: “Thank goodness we’re driving in a Taiwanese traditional blue truck. It carries as much love as we have, so let’s go!” The love is “carried” because it is a kenning for the load of pork. The English is a faithful translation of the Mandarin original. But what about the Seejiq translation? It is simpler:

|

M-adas |

=su |

siyang, |

m-uyas |

=su |

uyas, |

m-griq |

=su |

Ranpaw Cyueyni. |

|

af-carry |

=2sg.nom |

pork |

af-song |

=2sg.nom |

song |

af-drive |

=2sg.nom |

Lamborghini |

|

You’re carrying pork, singing songs, and driving a Lamborghini. |

||||||||

|

Uxay |

ka |

egu |

wah. |

|

neg-fut-cop |

nom |

much |

vcbl |

|

There won’t be too much. |

|||

It is simpler in two ways. First, in the Mandarin and English, the light truck carries a heavy load of love, but the Seejiq translation avoids potential confusion by referring the viewer to the visuals: the truck is carrying a load of pork (at 1:38 of the MV), which clearly represents love in figure 2 (2:42–2:51 of the MV). Second, the Seejiq translation is syntactically so regular, with its verb=subject object triplet, that it could serve as a pedagogical pattern. By singing along, a language learner can practise the pattern. A learner who has heard Yoku’s first song “Sinou” (which should be spelled sinaw) could then come up with Mimah=su sinaw, “You’re drinking wine”. A learner who has heard “Mkuung Ayug” and received a minute of grammatical instruction could convert qtaan, a Locative Focus form, to qmita, an Actor Focus form, to come up with Qmita=su Hakaw-Utux, “You’re seeing the Rainbow”. Rwahun could similarly be converted into rmaguh to produce a sentence such as Rmaguh=su lnglungan, “You’re opening your mind”.

Although simpler, the lyrics are nonetheless amusing and clever. The use of Ranpaw Cyueyni, meaning “Lamborghini”, as a translation of “get-rich vehicle” (meaning “light truck”) is amusing because such trucks are usually beat-up pick-ups. It also demonstrates the translators’ clever appropriation of foreign lexicon. According to Yoku, this particular translation was Principal Lituk Teymu’s idea. Although an elder, Lituk Teymu is evidently not at all resistant to linguistic change.

The translational trends I have been discussing apply to the remainder of the songs on the album. A final piece of evidence is not a trend, because it is unique, but it suggests that the purpose of the above trends is pedagogical. One of the songs is entitled “Malu Qtaan”, meaning “good-looking” – literally a good location-of-seeing. Its Mandarin translation – in this case, Yoku translated from Seejiq to Mandarin – is “媽滷個蛋” Mā Lŭ ge Dàn, “Ma braised an egg.” The Mandarin is a transliteration, a pronunciation that a language learner can refine. It is also memorable and an attempt to make language learning fun.

I can attest personally to the pedagogical effectiveness of Yoku’s translated lyrics. My then-five-year-old daughter and I sang along when “Jiyax Smipaq Babuy” was released on Christmas Eve, 2019. Going on three years later, she still remembers the chorus:

|

Jiyax |

s<m>ipaq |

babuy |

kuxul |

mi-su |

balay |

ksa |

ha. |

|

day |

af-slaughter |

hog |

love |

1sg-2sg |

true.truly |

like.this |

vcbl |

|

That’s how much I truly love you on hog slaughtering day. |

|||||||

My daughter learned it without knowing what the individual words meant, but in the meantime she has figured out at least the first three. Mnemonically, it helps that babuy sounds like the informal Taiwanese Mandarin term for father.

Has Yoku done anything to promote the use of her songs for language learning? On her public Facebook page (幽谷 Yoku Walis), which is followed by more than 40,000 people, she created a post (on 20 May 2020) entitled “A Seejiq Sentence a Week” accompanied by a 20-second video clip from “Jiyax Smipaq Babuy”. On her personal Facebook page (Yoku Walis), which is followed by just more than 3,600 people, she posts about her public performances, including for elementary school students (e.g., 4 January 2022). It may seem odd for Yoku to perform Seejiq hip hop for elementary school students, but youngsters in Taiwan have catholic tastes. In addition, Yoku uses her personal Facebook page as a platform for posts that foster Seejiq language learning: her own Seejiq language classes (e.g., 20 April 2022) and her experience with hosting and performing at language learning events (e.g., 30 March 2022). She also posted the perfect score she received on the intermediate language proficiency examination (8 March 2020). Finally, she has recently performed and explained her Seejiq hip hop on a TV variety show (23 April 2022).

6. Conclusion

By appearing on this television show and by narrating her quest for roots in Vanished Valley, Yoku Walis has become an ambassador for the Seejiq language and culture. She does not present herself as an activist like her compatriot Suming, nor does she adopt a stance of resistance as certain Indigenous hiphoppers in other settler states do (see in particular Mitchell, 2000, pp. 49–53). In her article on activist hiphoppers for whom art is a means of resistance, Taviano (2016) identifies translation as “a political act” (p. 282), but Seejiq hip hop is not explicitly political; I would describe it as “pedagogical” (cf. Schweig, 2022, p. 168).[2] A reformer, not a radical, Yoku Walis creates Seejiq hip hop to learn about her ancestral language and culture and to share this knowledge with her audience.

As I stated at the end of the section on the theoretical background to this article, the evidence I have gathered is stronger on the production of Yoku’s translated I-pop than on its consumption. One way in which scholars have dealt with the consumption of translated I-pop is by studying its use in language classrooms (Przybylski, 2018; cf. Szego, 2003, who discusses student translations of Hawaiian hymns). Przybylski’s study is noteworthy in the present context because it discusses the pedagogical use of Tall Paul’s Ojibwe hip hop, which Tall Paul translated from English into Ojibwe with the help of elders. If Yoku Walis’s Seejiq hip hop is ever used to teach Seejiq in a classroom, I could adopt a similar methodology to study its pedagogical efficacy.

I have, however, made a case for its potential efficacy. Through textual analysis, I have demonstrated that Yoku and her co-translators adopted strategies that produced simple, straightforward and memorable texts, strategies that can be summed up as pedagogical translation and which produced material for “casual language learning” (O’Connell, 2011). Young Indigenous recording artists who, like Yoku, have become alienated from their ancestral languages partly as a result of assimilatory national language policies in settler states around the world would tend, I hypothesize, to translate their lyrics pedagogically. Another follow-up task would be to test this hypothesis in other instances. Other case studies of translated I-pop would, of course, have to contextualize it.

Having adopted an approach to inclusive development “that accommodates both structure and agency” (Marais, 2018, p. 97), I situated Yoku’s Seejiq hip hop in the context of the government’s efforts over the past three decades to make up for the damage it had inflicted on Indigenous languages and cultures under martial law (1949–1987). In particular, I argued for the cost-effectiveness of the Indigenous-language GMAs. These awards may not have launched the I-pop trend, as Gideon Su, Yoku’s producer, claimed (2020, p. 11), because Samingad was singing in Puyuma and Biung in Bunun before the awards were introduced. But, at a minimal cost, these awards have contributed to the trend by motivating young recording artists to make I-pop albums, each one a contribution to linguistic and cultural development. GMA hopefuls may be partly motivated by the chance to raise their personal profiles, but what would do more to raise the profile of Seejiq than for Yoku Walis to win a GMA and enjoy fame and fortune from her hip hop?

In this regard, we should accept and even embrace the probably complicated motivations of settler states and Indigenous singers alike. President Chen Shui-bian may well have been more concerned about his re-election campaign in 2004 than he was about the revitalization of Taiwan’s Indigenous languages; and Yoku Walis may well wish to become rich and famous like her mentor, Aljenljeng Tjaluvie, in addition to developing the Seejiq language and culture. But if the Indigenous-language GMAs, whatever President Chen’s motivations for their initiation were, have contributed to Seejiq hip hop, whatever Yoku Walis’s motivations for its creation were, then from the perspective of inclusive linguistic and cultural development, I claim that the awards are beneficial.

In making this claim, I have followed Taiwanese usage and adopted development as a way of thinking about revitalization. “Development” is a reminder that any revitalization “make[s] it new” (Clifford, 2013, p. 299). Israeli, for instance, was created in the crucible of Hebrew (Zuckermann, 2020). It was created by language learners, including translators (Toury, 1985). This does not mean that Toury was right to claim that translators tend to become vectors of source-language “interference” in “weak target systems” (p. 8; italics original). In response to Toury’s article, scholars have argued, to the contrary, that minority language translators might consciously avoid source-language interference out of concern for a language’s loss of “particularity” (Cronin, 2003, p. 141). Cronin (1995, p. 86; 2017, p. 150) has always stressed that minority is a relation, not an essence, so he is well aware that whatever “particularity” a minority language has, change is inevitable. Cronin (2003) advocates “reflexion”, by which he means “critical consideration of what a language absorbs and what allows it to expand …” (p. 141; italics original), as a way for minority language translators to guide linguistic change. In a recent study of minority language translators, Kuusi and his colleagues respond to Cronin’s advocacy by noting that “the critical voices in our data are few and far between” (Kuusi et al., 2022, p. 156). Although our job as scholars is to consider translation critically, I think its importance to linguistic development can be overstated. Critical voices in my data are also few and far between. But, overall, the data suggest that, as long as endangered Indigenous minority languages such as Seejiq continue to be spoken, written, and sung, ordinary language-users, whether they translate or not, will find their own ways to develop them.

As I see it, Yoku and her colleagues are not a team of “tuggers” in a tug of war with the Mandarin-speaking majority; they are rather trapeze artists swinging one another back and forth and along, domesticating, foreignizing and developing innovations that transcend existing linguistic norms in either Seejiq or Mandarin. In this way, Yoku, Walis and Lituk are artists, and agents, of Seejiq linguistic and cultural development in contemporary conditions of mobility. Listening to “Mkuung Ayug” and “Jiyax Smipaq Babuy”, I can also imagine them riding in a Ranpaw Cyueyni – a Lamborghini – over the Rainbow, not into the traditional Seejiq afterlife but rather into “the after-life of translation”, a place where survival is “sur-vivre, the act of living on borderlines” (Bhabha, 1994, pp. 226–227; italics original).

References

32nd GMA viewership. (2021, August 23). Central news agency. https://www.cna.com.tw/news/amov/202108230164.aspx

Appiah, K. A. (2000 [1993]). Thick translation. In L. Venuti (Ed.), The translation studies reader (pp. 417–429). Routledge.

Barrett, R. (2016). Mayan language revitalization, hip hop, and ethnic identity in Guatemala. Language & Communication, 47, 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2015.08.005

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

Bu. (n.d.). The top fifteen little known facts about the Golden Melody Awards. Marie Claire. https://www.marieclaire.com.tw/entertainment/music/59656

Chen, C.-B. (2007). Voices of double marginality: Music, body, and mind of Taiwanese Aborigines in the post-modern era [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Chicago.

Clifford, J. (2013). Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the twenty-first century. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674726222

Comrie, B., Haspelmath, M., & Bickel, B. (2015). The Leipzig glossing rules: Conventions for interlinear morpheme-by-morpheme glosses. Department of Linguistics of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the Department of Linguistics of the University of Leipzig. https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/pdf/Glossing-Rules.pdf

Cronin, M. A. (1995). Altered states: Translation and minority languages. TTR: Traduction, terminologie, redaction, 8(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.7202/037198ar

Cronin, M. A. (2003). Translation and globalization. Routledge.

Cronin, M. A. (2017). Eco-translation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315689357

De Busser, R. (2019). The influence of Christianity on the Indigenous languages of Taiwan: A Bunun case study. International Journal of Taiwan Studies, 2(2), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1163/24688800-00202007

Del Hierro, M. (2016). “By the time I get to Arizona”: Hip hop responses to Arizona SB. In J. Berglund, J. Johnson, & K. Lee (Eds.), Native American music from jazz to hip hop (pp. 224–236). University of Arizona Press.

Everington, K. (2022, April 11). Academics urge prioritization of Taiwan's native languages over English. Taiwan news. https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/4503281

Faudree, P. (2013). Singing for the dead: The politics of Indigenous revival in Mexico. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822391890

Grin, F., & Vaillancourt, F. (1999). The cost-effectiveness evaluation of minority language policies: Case studies on Wales, Ireland and the Basque Country. European Centre for Minority Issues. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/25710/monograph_2.pdf

Hatfield, D. J. (2021). Voicing alliance and refusal in 'Amis popular music. In N. Guy (Ed.), Resounding Taiwan: Musical reverberations across a musical island (pp. 28–46). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003079897-2

Holmer, A. (2002). The morphology of Seediq focus. In F. Wouk & M. Ross (Eds.), The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems (pp. 333–354). Canberra Pacific Linguistics.

Jung, N. (2021, November 11–12). The use of K-pop in teaching Korean language. Innovation in language learning international conference. https://conference.pixel-online.net/ICT4LL/files/ict4ll/ed0014/FP/7613-TST5329-FP-ICT4LL14.pdf

Koskinen, K. & Kuusi, P. (2017). Translator training for language activists: Agency and empowerment of minority language translators. trans-kom: Journal of translation and technical communication research, 10(2), 188–213. http://www.trans-kom.eu/bd10nr02/trans-kom_10_02_04_Koskinen_Kuusi_Activists.20171206.pdf

Kuusi, P., Kolehmainen, L., & Riionheimo, H. (2017). Introduction: Multiple roles of translation in the context of minority languages and revitalisation. trans-kom: Journal of translation and technical communication research, 10(2), 138–163. http://www.trans-kom.eu/bd10nr02/trans-kom_10_02_02_Kuusi_Kolehmainen_Riionheimo_Introduction.20171206.pdf

Kuusi P., Riionheimo, H., & Kolehmainen, L. (2022). Translating into an endangered language: filling in lexical gaps as language making. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 274, 133–160. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2021-0019

Marais, K. (2018). Translation and development. In J. Evans & F. Fernandez (Eds.) The Routledge handbook of translation and politics (pp. 95–109). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315621289-7

McNaught, D. (2021). The state of the nation: Contemporary issues in Indigenous language education in Taiwan. In C. Huang, D. Davies, & D. Fell (Eds.), Taiwan’s contemporary Indigenous peoples (pp. 128–146). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003093176-8

Mitchell, T. (2000). Doin’ damage in my native language: The use of “resistance vernaculars” in hip hop in France, Italy, and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Popular Music and Society, 24(3), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007760008591775

O’Connell, E. (2011). Formal and casual language learning: What subtitles have to offer minority languages like Irish. In L. I. McLoughlin, M. Biscio, & M. Á. N. Mhainnín (Eds.), Audiovisual translation, subtitles and subtitling: Theory and practice (pp. 157–175). Peter Lang.

Przybylski, L. (2018). Bilingual hip hop from community to classroom and back: A study in decolonial applied ethnomusicology. Ethnomusicology, 62(3), 375–402. https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.62.3.0375

Schweig, M. (2022). Renegade rhymes: Rap music, narrative, and knowledge in Taiwan. University of Chicago Press.

Shulist, S. (2018). Signs of status: Language policy, revitalization, and visibility in urban Amazonia. Language Policy, 17(4), 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-017-9453-3

Simon, S. (2020). Yearning for recognition: Indigenous Formosans and the limits of indigeneity. International Journal of Taiwan studies, 3(2), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1163/24688800-00302002

Sterk, D. (2020a). Indigenous cultural translation: A thick description of Seediq Bale. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429243738

Sterk, D. (2020b). Translation and dialect dynamics in an endangered language. mTm, 11, 131–156.

Sturge, K. (2007). Representing others: Translation, ethnography and the museum. St. Jerome.

Su, G. T.-T. (2020). Discussion of a Taiwan Indigenous world music album: A case study of Vanished Valley [Master’s thesis]. Chinese University of Technology.

Susam-Saraeva, Ş. (2019). Interlingual cover versions: How popular songs travel round the world. Translator: Studies in Intercultural Communication, 25(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2018.1549710

Szego, C. K. (2003). Singing Hawaiian and the aesthetics of (in)comprehensibility. In H. M. Berger & Michael Thomas Carroll (Eds.), Global pop, local language (pp. 291–328). University Press of Mississippi.

Tan, S. E. (2017). Taiwan’s aboriginal music on the Internet. In T. R. Hilder, H. Stobart, & S. E. Tan (Eds.), Music, indigeneity, digital media (pp. 28–52). University of Rochester Press.

Taiwan plans to spend NT$30 billion to promote national languages. (2022, May 12). Focus Taiwan. https://focustaiwan.tw/culture/202205120022

Taviano, S. (2016). Translating resistance in art activism: Hip hop and 100 thousand poets for change. Translation Studies, 9(3), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2016.1190944

Tjaluvie, A. (2019). “Thank You” official music video. ABAO阿爆_阿仍仍. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cAp_IdqOuM

Tjaluvie, A. (2020). Open ancestral language classroom episode 9: Thank You.” ABAO阿爆_阿仍仍. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RT8hp5NCJHc

Toury, G. (1985). Aspects of translating into minority languages from the point of view of translation studies. Multilingua, 4(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.1985.4.1.3

Tsai, F. C.-L. (2010, August 4). Kapah (young men): Alternative cultural activism in Taiwan. Savage minds: Notes and queries in anthropology. https://savageminds.org/2010/08/04/kapah-young-men/

Tucker, J. (2019). Making Indigenous music popular: Popular music in the Peruvian Andes. University of Chicago. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226607474.001.0001

Venuti, L. (1995). The translator’s invisibility: A history of translation. Routledge.

Walis, Y. (2019a). Sinou. Taiwan PASIWALI Festival. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84K4EK0SUhY

Walis, Y. (2019b). Jiyax smipaq babuy. Tone Tv. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wow918ZWoow

Walis, Y. (2020). Mkuung ayug. Tone Tv. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yxy5bSt9gco

Zuckermann, G. (2020). Revivalistics: From the genesis of Israeli to language reclamation in Australia and beyond. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199812776.001.0001