Language diversity and inclusion in humanitarian organisations: Mapping an NGO’s language capacity and identifying linguistic challenges and solutions

Wine Tesseur (corresponding author)

Dublin City University

winetesseur@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4882-3623

Sharon O’Brien

Dublin City University

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4864-5986

![]() Enida Friel

Enida Friel

GOAL

Abstract

This article examines whether language diversity among staff in humanitarian organisations may affect inclusion and, if so, in what ways it does. We draw on the findings of a survey on staff’s language skills in the international NGO GOAL. We also draw parallels with practices noted in other international NGOs in previous research. Prior to the survey, data were lacking on the languages GOAL works in, which staff work multilingually, and whether gaps existed in language capacity and translation provision. The data provide evidence of the rich multilingual landscape in GOAL and reveal some patterns in the language use and multilingualism of staff. The survey investigates the notion that inclusion also has a linguistic dimension: staff and local communities speak a variety of languages, yet the main working language of the international humanitarian sector is English and, by extension, a handful of other major former colonial languages such as French and Spanish. Data-gathering such as that done in this study is important for two main reasons: without such data, INGOs cannot fully understand the level of exclusion that some of their staff may be facing because of language differences; and they are unable to grasp the extent to which they rely on the multilingual skills of their staff to provide ad hoc translation solutions that ensure effective communication and successful humanitarian assistance. The article aims to advance the debate on language challenges in the NGO sector by offering concrete data on informal translation and interpreting practices in one example that is representative of language practices in the international humanitarian sector. This contribution will hopefully encourage other international NGOs to collect similar data on language use and barriers that will help organisations to deal positively with the linguistic dimension of inclusiveness.

Keywords: inclusion; language diversity; informal translation; Core Humanitarian Standard; aid effectiveness

1. Introduction

Humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) aim to provide assistance and services in a timely and appropriate manner and in line with the needs of those living in crisis. To uphold and improve the quality of their work and their accountability to affected communities, the international NGO (INGO) sector has created various codes of conduct and guidelines, such as the Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) and the Sphere Handbook (CHS Alliance et al., 2018; The Sphere Project, 2018). Some of the content of these guidelines and professional codes relates to the principle of inclusiveness. For example, the CHS elaborates on the need for NGOs to have policies, processes and systems in place that will ensure the inclusion of local communities in humanitarian processes (CHS commitment 4, “Humanitarian response is based on communication, participation and feedback”). These policies, processes and systems will also guarantee equitable working practices in NGOs (CHS Commitment 8, “Staff are supported to do their job effectively, and are treated fairly and equitably”, The Sphere Project, 2018, p. 50).

However, what tends to remain an omission from these guiding principles is the notion that inclusion also has a linguistic dimension: staff and local communities speak a variety of languages, yet the main working language of the international humanitarian sector is English and by extension a handful of other major former colonial languages such as French and Spanish. The way in which the dominance of these languages affects the humanitarian sector’s aims and guiding principles of working inclusively is an area that is generally overlooked in discussions in the INGO sector. This prevails despite debates on inclusivity and the need to decolonise the aid system and to redress structural racism having increased in pace and depth over the past few years (Bond, 2021; Peace Direct, 2021).

Recent research conducted at the intersection of Translation and Interpreting Studies with Development Studies and Disaster Studies has already raised various issues regarding the low profile of languages and translation in development and humanitarian settings. These include the fact that INGOs tend not to plan for language needs as part of their long-term development projects nor do they plan for emergency responses (Federici et al., 2019; Footitt et al., 2020). INGOs generally do not collect basic data on the languages and literacy levels of local communities, which leads them to opt for ad hoc translation solutions. They frequently rely on multilingual aid workers, who have typically not been trained in language work and for whom translation is rarely part of their official job descriptions (Bierschenk et al., 2000; Federici et al., 2019; Footitt et al., 2020; Lewis & Mosse, 2006). Research has also shown that the dominant role of lingua francas in the sector, particularly that of English, can present barriers to aid workers’ performance at work and their career advancement, whereas skills in more locally used languages seldomly translate into an economic advantage and tend to be taken for granted in the case of national staff (Footitt et al., 2018; Garrido, 2020; Roth, 2019).

To overcome linguistic barriers and their potentially detrimental effect on aid delivery, authors (Federici et al., 2019; Footitt et al., 2018; Mancuso Brehm, 2019) have called on INGOs and donors to consider the role of languages more overtly by, for example, formalising multilingual communication strategies and collecting data on language needs, costs and benefits. Mancuso Brehm (2019) has argued that INGOs and donors “can improve their effectiveness simply by finding out what language skills the organisation already possesses and acknowledging and valuing them” (p. 537).

Indeed, INGOs have vast linguistic capacity; yet because they seldom collect data on the language skills of the staff and the way these skills are used at work, INGOs effectively miss out on two important parts of the inclusivity and equity puzzle. First, without such data, INGOs cannot fully understand the level of exclusion that some staff may be facing because of language differences. Secondly, INGOs are not able to grasp the extent to which they rely on the multilingual skills of their staff to provide ad hoc translation solutions to ensure effective communication and successful humanitarian assistance.

Following up on Mancuso Brehm’s (2019) suggestion, the current article aims to examine the link between inclusion and the language skills of INGO staff. It explores the ways language diversity among staff may affect inclusion in a humanitarian organisation and examines the role that translation and interpreting (T&I) play (or can play) in overcoming language barriers. We do so by drawing on the findings of a survey on the language skills of the staff in the international NGO GOAL and by drawing parallels with practices noted in other INGOs in previous research (e.g., Federici et al., 2019; Federici & O’Brien, 2019; Footitt et al., 2020; Tesseur, 2015, 2018).

In general, the article aims to advance the debate on the language challenges and opportunities in the sector. It does so by offering concrete data on informal T&I practices in one example that is representative of such practices in the international humanitarian sector at large. Our article aims to make two key contributions. First, to the INGO sector, the article offers a concrete, practical example of the way INGOs can collect data on language practices and can actively start dealing with the linguistic dimension of working inclusively. Secondly, to Translation and Interpreting Studies the article offers a new dataset and showcases the important role that translation researchers can play in collaborating with INGOs to raise awareness of language challenges and to suggest practical ways in which T&I solutions can lead to more inclusive ways of working.

2. Research context

The International NGO GOAL is currently active in 14 countries across various geographical regions, including Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Middle East, with its headquarters (HQ) in Ireland. In total, GOAL employs approximately 2,500 staff. The organisation does not have an overt institutional language policy that defines the languages it works in; but English functions as the organisation’s default lingua franca, particularly for communication between its HQ and the country programmes. However, English does not have official status in at least six of GOAL’s countries of operation. GOAL’s HQ has made available key documents used in the organisation in Arabic, French and Spanish and to a lesser extent in Turkish for staff in non-English-speaking countries. These include, for example, the organisation’s Code of Conduct and various policies, such as the Anti-Fraud, Child Protection, Conflict of Interest and Whistleblowing policies. These documents were translated by an external translation agency with which HQ has a contractual agreement. Meetings and training sessions organised by GOAL’s HQ are usually held in English, but HQ staff sometimes choose to host them in other languages, such as French or Spanish. In GOAL’s country programmes, field monitoring, verification and training usually take place in locally spoken languages, and communication with project participants is also accommodated as far as possible in local languages. Prior to the survey, data were lacking on the languages GOAL works in, which staff work multilingually, and whether gaps exist in language capacity and translation provision. Fostering inclusion is a principle that underpins GOAL’s programming (GOAL, 2019) and the NGO also aligns itself with the Core Humanitarian Standard in its work – in which inclusion plays an important role. By committing itself to conducting a staff language survey, GOAL as an organisation therefore made an active effort to recognise the important role that language plays in its operations, and in its efforts to operate inclusively.

GOAL’s current approach to translation as an organisation is fairly typical of that of international organisations in the development and humanitarian sector. A study by Federici et al. (2019), for example, sampled just over two dozen humanitarian organisations about their practices and issues of language access for affected communities in crisis settings; it found that there appeared to be no formal guidance on providing translated information to affected populations in the majority of the participating organisations. Nevertheless, there was widespread agreement among the study participants that providing language access was of key importance to humanitarian operations. Furthermore, accommodating language needs was necessary to achieve the humanitarian sector’s aim of two-way communication to enable humanitarian organisations to be more accountable to affected communities (CHS Alliance et al., 2018; IASC–Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2016). In addition, research by Footitt et al. (2020) indicated that institutionalised language policies and translation departments currently appear to exist in only some of the largest INGOs, such as Oxfam and Save the Children. In addition, the focus of these policies and departments is usually on providing written translation into a limited number of lingua francas (e.g., Arabic, English, French, Spanish) rather than on the more diverse language needs that NGOs’ project participants may require (e.g., oral translation into locally spoken languages, including languages that may not be written; provisions for low levels of literacy). As mentioned above, these studies also found that the translation needs in the work of INGOs are often met only on an ad hoc basis.

Despite their helpful findings, the interview data and policy analyses that these studies are based on have some limitations, that is, they provide little insight into how much time INGO staff spend on providing informal T&I services nor do they provide insight into how widespread the issue of the language barriers faced by INGO staff might be. In order to start filling these gaps, the survey posed the following overarching research questions:

1) What language capacity does GOAL possess and how are language skills used at work?

2) What is the role of recent technological developments in supporting staff with translation needs?

3) What are the gaps and challenges and what support is needed to ensure inclusive communication in GOAL’s work?

Overall, the aim of the survey was to provide more quantitative data to complement the qualitative data provided through other research. It aimed to do this by mapping which staff were using which languages at work, quantifying the time that NGO staff spent on language work and exploring the extent to which recent technological developments are providing a new route to more linguistically inclusive work practices.

3. Methodology and data

The survey presented in this article was conducted as part of a research project titled “Translation as Empowerment”, based at Dublin City University (Tesseur, 2019). The project aimed to investigate the critical role of translation in establishing an equal two-way dialogue between Northern NGOs and the people they work with in the Global South. GOAL was the official partner organisation. As part of the project, ethnographic fieldwork consisting of interviews, a staff survey and participant observations was conducted in GOAL’s HQ between October 2019 and March 2020 and it continued online after the COVID-19 outbreak until August 2020. The survey data constitute the core data analysed and presented in this article, although we refer to the interview data at specific points to clarify some of the survey findings. Both the ethnographic fieldwork and the survey study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee at Dublin City University.

The survey ran between December 2019 and January 2020 and was available electronically in Arabic, English, French, Spanish and Turkish. It was distributed via selected staff mailing lists, including GOAL HQ staff; country directors and assistant country directors; the global Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL) team, and regional directors. All GOAL staff members were free to participate and the recipients on the selected mailing lists were asked to distribute the survey more widely. The survey was preceded by a plain language statement and an informed consent form that described the research and its purposes in detail. The responses were anonymous.

Bearing in mind the three broad questions set out above, the survey consisted of eight questions (see Appendix). First, the respondents were asked to self-assess their written and spoken skills for each of the languages that they had mastered, according to the categories basic, intermediate and advanced. Whereas self-assessment has its limitations as a method of collecting accurate data on an individual’s language skills, we included it in the survey for two reasons. First, it is a quick and convenient method of collecting information on language skills among staff; secondly, actual linguistic ability was not the focus of the study. Therefore, if individuals had under- or over-estimated their skills, this would not have had a major impact on the study findings. Rather, the aim was to compose a general picture of who in the organisation spoke which language and at what level of mastery.

After asking the respondents to self-assess their language skills, the survey asked whether they used their language skills at work. They were asked to elaborate on which languages they used for which task and how frequently they used them. Then the questionnaire elicited information on what technical support (if any) the respondents were using to help them with their language needs, such as free machine translation (MT) tools (e.g., Google Translate), online dictionaries or other support. Next, the respondents were asked what additional support they would benefit from to improve the language skills that they used at work or to resolve the language challenges that they encountered. Finally, the respondents could add comments about anything else relating to the role of languages and translation in their work. The survey concluded by collecting demographic data such as gender and region in which the respondents were working.

In the discussion that follows, some of the comments left by the respondents are shared to illustrate key findings. These are arranged by survey language and the respondent number: for example, Respondent-EN 28 refers to the 28th respondent who participated in the English-language survey.

4. Findings

4.1 Respondents’ background

A total of 117 responses were received across the different language versions: 70 for the English survey, 26 for French, 19 for Spanish, two for Arabic and none for Turkish. In total, 45% of the respondents were based in the GOAL HQ, 28% in the Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) region, 19% in sub-Saharan Africa, 4% in the Middle East; 4% were roving. For the Arabic, French and Spanish surveys, the language that the participants chose to take the survey in largely corresponded to the geographical region where they worked. For the English survey, 70% of the respondents were from HQ, 17% were based in sub-Saharan Africa, 7% were roving, 4% were based in the Middle East and 2% in the LAC region.

Overall, an acceptable balance was obtained regarding gender and there was a good spread of representatives from different types of job role. Of the participants, 57% identified as female, 41% as male and 2% indicated “prefer not to say”. Regarding job roles, 50% of the participants in the English survey worked in programming, with 41% working in systems support roles such as information technology (IT), finance, logistics, procurement, compliance and audit. A further 6% worked in External Affairs roles and 3% were senior management. In the French, Spanish and Arabic surveys, the number of respondents working in programming was higher, that is, 65% in the French and 85% in the Spanish survey. The remainder of the French and Spanish respondents worked in systems support, apart from one French-speaking director. Both of the respondents in the Arabic survey worked in programming. Because the responses to the Arabic survey were low, the analysis that follows takes into account only the Arabic answers to the open-ended questions.

4.2 Respondents’ language skills

The respondents reported language skills in 35 languages, including African, Asian, Latin American and European languages, with skill levels ranging from basic to native speaker. Most of the participants spoke more than one language, with a mere seven out of the 117 stating that they spoke one language only (five were English speakers; two were Spanish speakers). We recognize that the high level of multilingualism may not be representative of all GOAL staff, because people with multilingual skills may have been more likely to participate (this is despite the survey email encouraging all staff to participate, including those who were monolingual). Nevertheless, the data provide evidence of the rich multilingual landscape in GOAL. Furthermore, they are useful in establishing some patterns in the language use and multilingualism of the staff.

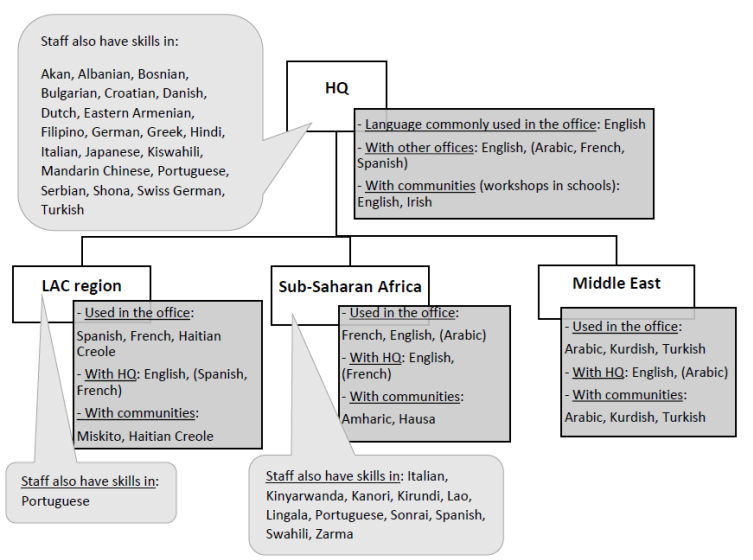

Figure 1 maps the languages used in GOAL offices in its four regions of operation, with languages that were used less frequently placed in parentheses. The figure also indicates other languages that staff have skills in but which were not typically used at work. The languages spoken by roving staff were considered part of the HQ group.

Figure 1

Languages spoken by GOAL staff mapped according to region

Among HQ and roving staff, only three participants indicated having skills in just one language. A further 11 participants spoke their native or first language, usually English, and had basic skills in one other language, typically French or Spanish. This means that 74% of the respondents in HQ or international roles spoke two or more languages at an intermediate or higher level. One of the reasons for this high level of multilingualism (apart from the potential respondent bias mentioned above) is that 20 out of 54 respondents in this group had a first language that was not English. Because the respondents needed English for their job, this made them highly proficient in at least two languages.

The language skills of GOAL’s staff in country programmes also showed some notable patterns. For example, the respondents in the French survey all spoke more than one language, with the majority having skills in three languages. The usual pattern was skills in one or more local languages, such as Haitian Creole (12 respondents), Hausa (5), Zarma (3), Kanori (1) or Sonrai (1), combined with (advanced) French skills and some English skills (usually at a lower level). Multilingualism in the Spanish survey was mostly Spanish with English skills. One respondent noted skills in the indigenous language Miskito and two other respondents had skills in Portuguese.

Because English is the working language of GOAL’s HQ, the expectation was that most respondents would have a high command of English. However, relatively low levels of English were reported by participants in the French and Spanish surveys, particularly for spoken English. Table 1 presents an overview of French- and Spanish-speaking respondents’ self-reported levels of English.

Table 1

Respondents’ self-reported levels of English in the French (FR) and Spanish (ES) survey

|

Spoken English |

FR (n= 26) |

ES (n= 19) |

TOTAL (n=45) |

% |

|

Written English |

FR (n=26) |

ES (n=19) |

TOTAL (n=45) |

% |

|

None |

1 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

|

None |

1 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

|

Basic |

13 |

8 |

21 |

47 |

|

Basic |

7 |

6 |

13 |

29 |

|

Intermediate |

5 |

2 |

7 |

15 |

|

Intermediate |

10 |

7 |

17 |

38 |

|

Advanced |

6 |

7 |

13 |

29 |

|

Advanced |

7 |

5 |

12 |

27 |

|

Native |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Native |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

Taking the data from the French and Spanish surveys together, 47% (21 out of 45 respondents) indicated that they had a basic level of spoken English only and an additional 7% (three respondents) said that they did not have any spoken English skills. The respondents self-reported higher levels of written English than of spoken English: 29% said their written English was at a basic level (vs 47% for spoken English), whereas 38% said their level was intermediate (vs 15% for spoken English). As noted, the participants self-reported their skill level and they may therefore have under- or over-estimated their abilities. Nevertheless, this information is useful because the self-reported levels give an indication of the staff’s confidence in using these languages. The reported low levels of spoken English may have implications for verbal training and meetings with HQ. For example, staff who have a low level of spoken English and/or who have low confidence may struggle to understand information, to ask questions or to contribute to a session. In other words, it may inhibit them from participating fully in instances where training or meetings are conducted in English only.

4.3 Languages at work

Whereas English is the main working language in HQ, staff who are based there and those who are roving (n=54) also used their intermediate or advanced skills in French (14 respondents), Spanish (13), and Arabic (3) to communicate with colleagues in GOAL country offices. These skills were mostly used for Skype and telephone calls, online chats or instant messaging, and to write and read emails. Three respondents used their French and/or Spanish skills every day and six respondents reported that they relied on their French, Spanish or Arabic skills weekly. It is noteworthy that three of these respondents indicated spending a considerable amount of time on translating documents and training materials, verifying the accuracy of translations, interpreting for colleagues or delivering training in Spanish or French. One respondent described their language work as follows:[1]

On average, I spend 5 hours per month working in French. But in addition: When I prepare training materials, this amount may drastically increase to full time for a few days or weeks. Example 1: 2 years ago, I prepared … training materials in French; this took me 4 full weeks of my working time (about 100 slides + training exercises). Example 2: last year, I verified translation of 2 training materials that were translated by a translation company. It took me each time 3 to 5 days as many adjustments were required. Last year, I performed 2 Field visits [in another language in two countries] (4 weeks duration in total). I am also using [a third language] a few times/year. I am reading in [a fourth language] a few times/year. (Respondent-EN 28)

The remaining respondents based at HQ used their Arabic, French or Spanish skills less frequently. When they did use these skills, this was usually during visits to country offices. It was also notable that 25% of those who had an intermediate or higher level of French or Spanish never used these language skills in their job, therefore indicating an underused skillset.

The language skills that staff used in GOAL’s country offices depended on their geographic location. French was widely used by colleagues in countries where French holds official status, although for 19 of 26 respondents it was not their first language. Some participants also mentioned using local languages when working with communities. In the office, staff who had advanced English generally used these language skills every day. Those who had a basic level of proficiency relied on English less, sometimes never, although seven out of 14 respondents who had no English or spoke only broken English indicated that they nevertheless used English occasionally to communicate with HQ or to access documents related to GOAL’s work.

A similar pattern emerged in the Spanish survey, where those with advanced English skills relied on these skills daily, whereas those with limited skills used their English only occasionally in emails, on Skype or to read documents. Those with no or only basic English skills relied on automated translation tools to support them with some basic communications or they sought the help of colleagues with advanced skills to interpret for them on calls or to translate documents. Five in-country-based staff across the English, Spanish and French surveys indicated that they frequently translated documents between English and French/Spanish/Arabic or in some cases into or from locally used languages such as Kurdish.

4.4 Use of technical tools to support language mediation

The most popular language tool that staff relied on was free automatic translation software such as Google Translate. In the English survey, 63% said that they used such tools at work. In the French and Spanish surveys this usage increased to 81% and 85% respectively. The use of free translation software far outstripped that of online dictionaries, which were used by 19% of the respondents in the English survey, 58% in the French survey and 31% in the Spanish survey. Although the widespread use of free translation software is perhaps not surprising, its usage does raise questions about the content that staff are translating with these tools. The interview data collected as part of the Translation as Empowerment project are not part of the analysis here, but we can nevertheless add that this interview data suggested that the staff were mainly using these tools as support when writing emails or to help them understand the gist of documents (for a more elaborate discussion of this point and of the interview data, see Tesseur, 2023). Whereas these examples constitute relatively low-stakes translation, caution is nevertheless in order, especially when staff are working with confidential and sensitive data (ibid). Furthermore, as the use of MT continues to grow globally, the need for training in a new skillset, namely, MT literacy (Bowker & Buitrago Ciro, 2019), becomes increasingly important. The potential need for more guidance and training specific to the NGO sector is a topic that we revisit in our discussion section.

4.5 Additional support needs

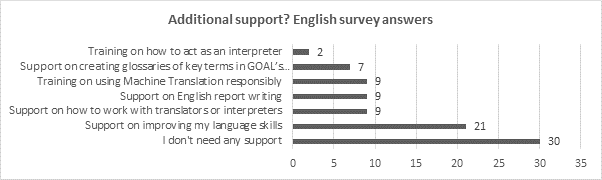

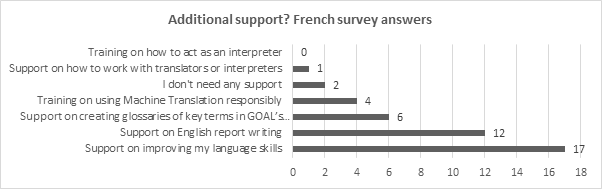

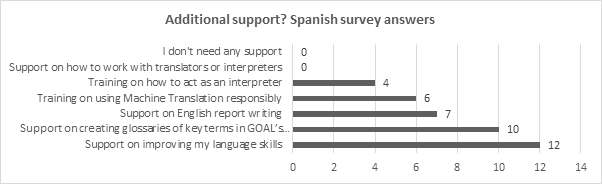

The respondents were asked what additional language support they would benefit from to improve the language skills they used at work or to respond to the language challenges that they faced in a professional context. The question contained a list of seven predefined answers and it was also possible for the respondents to add more options (see Appendix). They could choose to provide as many answers as they wished. Figures 2, 3 and 4 present the answers that the respondents selected in the English, French and Spanish surveys, with the options ordered from lowest to highest number of responses.

Figure 2

Additional support answers for English survey

Figure 3

Additional support answers for French survey

Figure 4

Additional support answers for Spanish survey

The most striking difference between the data from the English survey versus the French and Spanish surveys is the extent to which support was considered necessary. The French and Spanish survey data indicated a strong demand specifically for English-language support. In the French survey, only two out of 26 respondents (8%) indicated no need for support, and none did so in the Spanish survey.

Many respondents left comments in the “other” option that detailed their additional needs. In these comments, 84% in the French survey (22/26 respondents) and 79% in the Spanish survey (15/19) asked for support with English, either through support for improving their language skills or support in writing project proposals and reports in English.

In contrast, in the English survey, 30 out of 70 respondents (43%) said that they did not need any support. A further 13% (or 9/70) indicated a need for support specifically with English writing, even though they had completed the survey in English. These findings further underline the important role that English plays in the organisation, particularly in its HQ and in the sector at large: 41 out of 70 respondents in the English survey spoke English as their first language. Many of these respondents therefore did not perceive a need for support, because their first language was widely used in the sector and the organisation. Yet some of the remaining respondents did ask for support in the other key languages of the organisation: French (10), Arabic (8) and Spanish (5).

4.6 Open comments

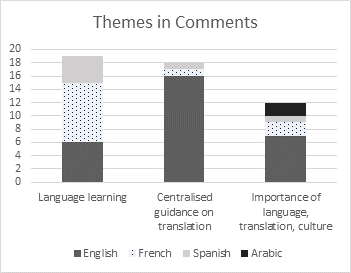

The final question gave the respondents the opportunity to share further reflections on the role of languages in their work. In the English survey, 27 respondents left comments, the French survey received 12 comments, and the Spanish survey six. Both participants in the Arabic survey also left comments. We took these into account for the description below. The responses were imported into the qualitative analysis software NVivo and were sorted according to emergent codes, which helped with identifying common themes. Figure 5 represents the identified themes with a break-down per language.

Figure 5

Coded themes in comments

The theme that was discussed most widely was that of language learning. The 19 comments on this topic can be further subdivided into seven responses that dealt with personal development (a desire to improve one’s language skills) versus 12 responses that took a more institutional point of view and emphasised the need for the organisation to be more proactive in encouraging language learning and to give language skills more prominence in recruitment. The idea that the organisation should establish a language training or exchange programme was one that was mentioned in several comments. Some respondents placed emphasis on the fact that more English speakers working in HQ or in international roles should make an effort to learn other languages, including local languages (Respondent-EN 43) and key languages of the organisation such as Spanish (Respondent-EN 9; Respondent-ES 6). Table 2 presents a selection of comments that focus on the institutional perspective.

Table 2

Comments on language learning in GOAL

|

Respondent-EN 9 |

More HQ staff should be able to speak other languages where GOAL has country offices and implements programmes. GOAL should identify the main languages in which it operates and offer language courses to staff to learn those languages. |

|

Respondent-FR 17 |

Créer un cadre de formation en anglais pour le staff francophone. [Create a training framework in English for French-speaking staff.] |

|

Respondent-ES 6 |

Es importante que si GOAL tiene presencia en la región LAC, mas staff en Dublin se esfuerze por aprender español asi como muchos en HN se esfuerzan por aprender ingles. [It is important that if GOAL has a presence in the LAC region, more Dublin-based staff should make an effort to learn Spanish just like staff in Honduras make an effort to learn English.] |

|

Respondent-ES 13 |

GOAL debería tener un programa que fomente el intercambio entre empleados para que fortalezcan el uso de idiomas. [GOAL should have a programme that encourages exchanges between employees to strengthen the use of languages.] |

It is important to emphasise that these are the perceptions of the staff and that these views do not always correlate with actual practice. For example, GOAL does encourage and provide staff with language-training opportunities on a case-by-case basis when a specific need is identified. Moreover, all GOAL staff with an email address have access to online courses in English, French and Spanish up to intermediate level through the organisation’s online learning platform. Finally, desk officers in HQ do generally speak the lingua franca used in the region they oversee (e.g., French, Spanish) and, as indicated by the survey findings, some staff in other support functions also speak Spanish or French.

Another key theme was the need for more centralised guidance on translation. Most comments were from participants in the English survey. As represented in Table 3, several subthemes emerged, such as requests for templates and organisational documents to be provided by HQ in other languages, requests for guidance on when it was appropriate to commission external translation (considering the costs involved), and suggestions about establishing an internal translation unit and learning from other INGOs.

Table 3

Comments on the need for more guidance on translation

|

Respondent-EN 47 |

How organisationally we can translate so many of our English documents, learning, newsletters etc. into various languages for our colleagues in various countries. That system could be centralised? How do other agencies manage this? |

|

Respondent-EN 55 |

Integrate automatic translators into software to enable data-sharing. |

|

Respondent-EN 61 |

I have … used GOAL document translation service-provider to do official translation of a survey questionnaire but this can prove expensive if the document is lengthy. It would be great to have in-house capacity for this. |

A recurring theme in 12 comments across all the language surveys was the fact that language, translation and cultural appropriateness were of key importance to GOAL’s work. The staff engaged with this theme from various perspectives: for example, in the context of safeguarding information and identities and fraud-prevention and of the relationships between GOAL and local communities or between international and national staff. Comments emphasised the importance of working in local languages, including Irish, and of carefully considering the accuracy and cultural appropriateness of key vocabulary.

Table 4

Comments on the importance of language, translation, and cultural awareness for GOAL

|

Respondent-EN 10 |

I believe that Translation and Interpreting is, and should be, a big part of international organisations; especially ones who deal with so many different cultures on a daily basis. Making the effort to operate in their native tongue helps with being an accepted entity in whatever crisis. |

|

Respondent-EN 14 |

Precise translation (in the local language used in-country) for Safeguarding terms is very important as sensitive terms are needed to explain various types of abuse and harm. Very often, different terms/slang words can have different meanings hence decreasing our efforts to prevent sexual exploitation and abuse. |

|

Respondent-EN 50 |

I think the role of language and translation is a topic that may have been neglected in our sector. It does certainly require resourcing, especially when it comes to communicating with beneficiaries and local groups or organisations. It should not be expected that they speak English, or exclude them simply because they do not speak English. I am not saying that this is the case in the sector, but unless resourced, we do run into those risks. |

5. Discussion and conclusion

The data reveal insights into the linguistic characteristics of much of GOAL’s office-based work. We here discuss how some of the emerging survey findings on language skills and use may influence efforts to foster inclusion. The survey findings show that although staff claim to possess skills in a wide variety of languages, there is not necessarily a match between this multilingual capacity and GOAL’s multilingual working practices, particularly for collaboration in the organisation. From the perspective of HQ, we saw that staff were impressively multilingual in 24 languages, but many of these languages did not play a role in the functioning of the organisation. Apart from English, the key working languages for international collaboration in GOAL are French, Spanish and Arabic, but the number of respondents from HQ who had an intermediate or advanced level of proficiency in these languages and used these skills regularly at work was limited. In the regional offices, we saw that some colleagues were bi- or multilingual, but that many staff members estimated their level of English skills to be relatively low. Corresponding to this low-level self-assessment, the French and Spanish survey respondents indicated using or wanting to avail themselves of more language support: first, there was heavy reliance on free automatic MT and, secondly, staff asked for support with their English skills. These findings point to the challenges and limitations of non-English-speaking staff: for example, in accessing information, writing reports and other documents in English and participating actively in meetings hosted in English.

These findings corroborate those of previous research on the role of languages and linguistic capacity in INGOs, including among other organisations such as Christian Aid, Oxfam GB, Tearfund and Save the Children UK (Footitt et al., 2018, 2020; Roth, 2019). These studies reported that INGO staff whose first language was not English felt at a disadvantage regarding career advancement. Footitt et al. (2018: 6) also describe the challenges non-English-speaking staff face when trying to convey the dynamism of community activities in reports that have to be written in English.

As noted in the introduction, previous research also indicated that much of the translation work in INGOs happens on an ad hoc basis. The survey data further demonstrate that some staff in HQ and in country programmes spend considerable time on translation, both written and oral. These informal translation practices, which make an important contribution to INGOs’ aims of working inclusively, and the widespread use of MT by staff, indicate a need for training in the INGO sector as a whole. Whereas professional training in translation or interpreting takes years, guidance on and training in some basic principles could help INGO staff to improve their practice. For example, to ensure the appropriate and ethical use of MT, some basic training in MT literacy would be useful – that is, learning how free MT software works, understanding that the text you enter is typically used to train the engine and may be shared with others and gaining insight into when it is appropriate to use such software (Bowker & Buitrago Ciro, 2019; Canfora & Ottmann, 2020). In response to the survey results, we have compiled a list of existing basic resources which may be useful to INGOs at large (Tesseur, 2021).

The comments that staff shared in the survey were characterised by requests for more institutional support to meet language needs and resolve challenges. The staff linked language to values and principles that are of key importance to the organisation, such as inclusion and respect (as explained in its 2019 strategy note; see GOAL, 2019). Returning to our point about language inclusion, we interpret the survey data as suggesting that “language” should be added in research and internal efforts in an NGO which aims to understand the potential mechanisms that can unwittingly create or exacerbate exclusion. This is relevant not only to GOAL but also to the INGO sector at large, which aspires to abide by principles of inclusiveness.

For GOAL, conducting the survey and discussing its findings with the staff led to an increased awareness among the staff of language barriers and to the potential role that translation can play in ameliorating some of the challenges. Discussions on what action can be undertaken to resolve some of the identified challenges took place during two internal webinars organised by the research team to share the survey findings in June 2020, and in which 58 staff members participated. Overall, the survey, the webinars and the semi-structured interviews that were also conducted during fieldwork led to some practical action that staff took at a personal or a team level. For example, in one team, non-English-speaking staff who found it challenging to present in English during meetings were asked to collaborate with a colleague who speaks better English to assist them with interpreting or presenting during meetings. Following this example, it has now become common practice that non-English speakers are helped in this way during meetings or presentations. In another team, language skills – including skills in local languages – have come to be incorporated into the team’s skills framework and in personal development plans. Finally, GOAL’s IT service has provided training to show staff how to use functions such as live captions and transcription in different languages in Microsoft Teams and automated translated subtitles in PowerPoint. These tools are now being used increasingly by staff during meetings and conferences.

By reporting on the survey activities in this article we drive home the point that coming to a more conscious approach to language inclusivity does not necessarily require a large investment in resources and planning. Rather than creating an organisation-wide policy as a first step (which may then not lead to any actual change in practice), our approach shows that starting with raising awareness of language barriers and then devising small, feasible initiatives is a useful starting point that can quickly contribute to positive inclusive change. In the longer term, the positive results of such an approach can hopefully lead to larger organisation-wide policies that are widely understood and supported by all staff, including senior management.

With this article it is therefore not our intention to make strong recommendations on policy as a first course of action. We recognise that organisation-wide policy choices can be challenging, because a consensus needs to be reached first and choices on internal language use typically come with commitments to translation, which may be costly and are time- intensive (Meylaerts, 2011). However, we do argue that it is pertinent for organisations which aim to foster inclusion to collect data on language needs, capacity and cost, and to reflect actively on their language choices and the way they can affect inclusiveness, both internally in the organisation and in INGOs’ work with local communities. Translation and Interpreting Studies scholars are well placed to engage in and contribute to such discussions by suggesting ways in which T&I solutions can contribute to overcoming language barriers and devising multilingual ways of working that fit in with humanitarian organisations’ values and aims of working inclusively.

Finally, we would also like to acknowledge some of the limitations of the evidence presented and to suggest future avenues for research. Despite providing insight into GOAL’s rich multilingual capacity, we recognise that with 117 responses the survey data do not represent the views and experiences of all GOAL staff; nor will the data be representative of the working realities of every INGO, such as those which have roots in non-Anglophone countries. Secondly, the survey findings provide some quantifiable data on how widespread the phenomenon is of multilingual staff using their language skills at work; but it does not provide detailed insight into the ways in which country staff communicate with project participants in local languages. Thirdly, the survey data do not explain the why or how of specific language choices. We also have little understanding of the extent to which the low levels of English of certain staff actually cause problems, such as misunderstandings of project objectives.

Such insights are difficult to gain through one study, and particularly through a survey. As noted in the methodology section, complementary data were collected through interviews and ethnographic observations, and future publications will therefore provide more richly grained interpretations (e.g., Tesseur, 2023). In addition, the current study should be complemented with research that focuses on and is conducted by researchers and practitioners based in other locations, in other organisations, and who may work in different languages. Such contributions will further enrich our understanding of the challenges of communicating inclusively, and of the way T&I can contribute to overcoming them.

Funding acknowledgement

This project has received funding from the Irish Research Council and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 713279.

References

Bierschenk, T., Chauveau, J.-P., & Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. (Eds.). (2000). Courtiers en développement: Les villages africains en quête de projets. Karthala.

Bond. (2021). Racism, power and truth: Experiences of people of colour in development. Bond. https://www.bond.org.uk/sites/default/files/resource-documents/bond_racism_power_and_truth.pdf

Bowker, L., & Buitrago Ciro, J. (2019). Machine translation and global research: Towards improved machine translation literacy in the scholarly community. Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787567214

Canfora, C., & Ottmann, A. (2020). Risks in neural machine translation. Translation Spaces, 9(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00021.can

CHS Alliance, Groupe URD, & Sphere Association. (2018). Core humanitarian standard on quality and accountability: Updated guidance notes and indicators 2018. https://corehumanitarianstandard.org/files/files/CHS_GN%26I_2018.pdf

Federici, F. M., Gerber, B. J., O’Brien, S., & Cadwell, P. (2019). The international humanitarian sector and language translation in crisis situations. INTERACT The International Network on Crisis Translation.

Federici, F. M., & O’Brien, S. (Eds.). (2019). Translation in cascading crises. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429341052

Footitt, H., Crack, A. M., & Tesseur, W. (2018). Respecting communities in international development: Languages and cultural understanding. http://www.reading.ac.uk/web/files/modern-languages-and-european-studies/Listening_zones_report_-EN.pdf

Footitt, H., Crack, A. M., & Tesseur, W. (2020). Development NGOs and languages: Listening, power and inclusion. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51776-2

Garrido, M. R. (2020). Language investment in the trajectories of mobile, multilingual humanitarian workers. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1682272

GOAL. (2019). GOAL Strategy 2019–2021: Alliance, ambition, action.

IASC–Inter-Agency Standing Committee. (2016). The grand bargain: A shared commitment to better serve people in need.

Lewis, D., & Mosse, D. (Eds.). (2006). Development brokers and translators: The ethnography of aid and agencies. Kumarian Press.

Mancuso Brehm, V. (2019). Respecting communities: Languages and cultural understanding in international development work. Development in Practice, 29(4), 534–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1569591

Meylaerts, R. (2011). Translational justice in a multilingual world: An overview of translational regimes. Meta: Journal Des Traducteurs, 56(4), 743. https://doi.org/10.7202/1011250ar

Peace Direct. (2021). Time to decolonise aid: insights and lessons from a global consultation.

Roth, S. (2019). Linguistic capital and inequality in aid relations. Sociological Research Online, 24(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780418803958

Tesseur, W. (2015). Transformation through translation: Translation policies at amnesty international [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Aston University.

Tesseur, W. (2018). Researching translation and interpreting in non-governmental organisations. Translation Spaces, 7(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00001.tes

Tesseur, W. (2019). Translation as empowerment: Translation as a contributor to human rights in the global south. https://sites.google.com/view/translation-as-empowerment

Tesseur, W. (2021). List of free language and translation support resources for NGO staff. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1HwxwWGOunidZ0rjSD9H59lsYeXDCqMIKNCzPwlXaQIc/edit?usp=sharing

Tesseur, W. (2023). Translation as social justice: Translation policies and practices in non-govern-mental organisations. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003125822

The Sphere Project. (2018). The Sphere handbook: Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. http://handbook.spherestandards.org/en/sphere/