Performing political reparation:

Public service interpreters’ dispersed practices

for social justice

Deborah Giustini

Hamad Bin Khalifa University

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8967-193X

Abstract

This study examined the activities of spoken-language public service interpreters who are engaged in supporting social justice and marginalized communities across a variety of institutional settings in the United Kingdom. By drawing on a practice theory approach, it argues that public service interpreters’ ad-hoc social and communicative activities in and beyond interpreted encounters are practices of “dispersed activism”. Although lacking the organized and collective character that characterizes a social movement, dispersed activism can work towards changing unjust systems. Based on a dataset of qualitative interviews, the study revealed a group of public service interpreters as architects of political reparation who shape both communication interactions and their own professional conduct towards localized societal transformation in power-laden settings. In addition to conceptualizing public service interpreting activism as non-formalized equity-oriented practices, the study reveals how aiming at social justice imposes challenges on the interpreters’ emotional, bodily, and material involvement, with implications for the negotiation of norms of neutrality and non-engagement.

Keywords: practice theory; dispersed activism; social justice; public service interpreting; political reparation

1. Introduction

Critically engaged research in interpreting studies has increasingly highlighted interpreters’ instrumental role in bringing about cultural and ideological change as they leverage their language and communication agenda in settings and activities that support minority, marginalized, or migrant groups (Federici, 2020; Inghilleri, 2007), social movements such as Black Lives Matter (Napier et al., 2022), queer activism (Baldo et al., 2021), deliberative democracy (Doerr, 2018), the alter-globalization movement (Boéri, 2012; Boéri & Delgado-Luchner, 2020) and the COVID-19 pandemic crisis (Boéri & Giustini, 2023, 2024). In particular, social justice has become central to studies on public service interpreting (PSI) (Bancroft, 2015; Monzó-Nebot & Mellinger, 2022; Prunč, 2012). The role of public service interpreters (PSIs) is often invoked with a view to reducing disparities across institutional settings, ensuring that those who do not speak the official language(s) are on an equal footing with those who do. Therefore, PSI is associated with a positive impact, since it “weds issues of language and culture to concepts of social justice and equity” (Bancroft, 2015, p. 218). As Prunč remarks through the words of Zygmunt Baumann, PSI is in fact often perceived as dealing with “the wasted lives and the outcasts of modernity” (Prunč, 2012, p. 4) such as marginalized communities of forced migrants caught in armed conflicts. Nonetheless, PSI settings such as healthcare, courts, and asylums are often incubators of power asymmetries and discrimination that ripen in communication. In this regard, perhaps the most visible iteration of the transformative power of PSI lies in interpreters’ interventions in communicative encounters that overcome the deontological status quo of professional neutrality and non-engagement (Giustini, 2019; Skaaden, 2019; Valero-Garcés & Tipton, 2017).

Despite the role of PSIs in promoting respect for and recognition of “Otherness” – that is, the populations of speakers of languages other than the system’s major language (Wallace & Monzó-Nebot, 2019, p. 7) – in the communicative space, their activities do not necessarily fall under social justice. Established theorizations frame the positioning of interpreters vis-à-vis social justice as various forms of collective action crystallized through the politics of language, generating a space of resistance to and inversion of the symbolic hegemonic order (Baker, 2013; Boéri, 2022). In this respect, many activist interpreting groups align themselves explicitly with horizontal and prefigurative movements, establishing loose protocols for organizing and providing services. Accordingly, they function as fluid but no less effective networks (Baker, 2013; Boéri, 2012, 2022). However, opportunities for interpreters who work in PSI to organize and support social justice formally are more constrained. This limitation stems from the dispersed nature of PSI across various organizations, service provisions, and communicative encounters. In addition, the global trend towards neoliberalism, characterized as it is by marketization and individual responsibilization, further restricts interpreters’ ability to advocate social justice in their professional roles (Kerremans et al., 2018; Nordberg & Kara, 2022).

Harnessing the power of these contributions, and drawing upon my work on interpreting as “political reparation” (Giustini, 2019), this study examined spoken-language PSIs’ activities, and their aggregation as a prism of social change, leveraging a practice-based approach. This is a theoretical–empirical orientation that foregrounds practices – routinized regimes of materially mediated doings, sayings, knowing, and ways of relating – as the building blocks for understanding social phenomena (Nicolini, 2012; Schatzki, 2002; Shove et al., 2012). Placing practice at the core of analysis, this study interrogated interpreters’ social and communicative activities as being non-organized politically. In this article it is argued that PSIs’ practices, though not conforming to “classic” models of intentional, collective, ethical action in the translation and interpreting fields, do have a societal impact and can work to change unjust systems. More specifically, the article posits that PSI practices can function as “dispersed collective activity” (Welch & Yates, 2018) as aggregate effects arise from socially engaged practices, leading to the development of further outcomes (e.g., social justice). A practice-based approach therefore helps us to appreciate the nuances of PSI as equity-oriented work that fills the liminal space between linguistic, cultural, social, and political divides. Taking these threads together, the study investigated these questions: Through which processes of dispersed collective activity do PSI practices give rise to social change and justice? What are the outcomes of these processes?

The article responds to these questions through a qualitative study of PSI in the United Kingdom – a context marked by language diversity but also by stark inequalities in public services (Giustini, 2020). The study finds that interpreters, through the practices they carry out, enact social justice as part of their professionalism, accountability, and responsibility in public services. Drawing upon their skills, knowledge, and emotional investment, they move through the communicational performance by striving towards users’ benefit; in turn, they generate a contingent impact for both users and institutions. Importantly, the study also finds that although the interpreters did not explicitly identify with any formalized collective enterprise, they held some sort of latent group identity as socially engaged practitioners who directed their aims towards “restorative justice” (Ahmed, 2013, p. 197). Restorative justice indicates transformative social change in which the cultural politics of language use and discourse mediates social and embodied encounters with the Other. Finally, and closely related to this, the study highlights that, far from their normative apolitical role, the interpreters negotiated neutrality according to their own judgement of the parties, the communication, and the specific situation.

This article therefore makes three original contributions to the interpreting literature. First, it contributes theoretical groundwork by accounting for the justice-oriented actions of PSIs as social practices. It puts to work Schatzki’s (2002) version of practice theory and Welch and Yates’ (2018) practice-based conceptualization of social movements to theorize non-formalized, non-institutionalized, yet equity-inspired practices of interpreting as forms of activism. Second, the article pays attention not only to the ostensible spoken-language practices of PSIs, but also to the complexities of managing their professional commitment to marginalized communities and stigmatized settings, such as those of refugees and asylum-seekers. It does so by providing a practice-sensitive stance that seeks to expose the injustices visited upon PSI users and the valuable contributions of PSIs. Finally, in paying empirical attention to the practices of PSI in the United Kingdom, the article establishes these as a form of political reparation (see Giustini, 2019) building upon Ahmed’s (2013) concept of restorative justice. Through the attention it devotes to political reparation, the article highlights the dispersed efforts to redress the systemic injustices enacted by interpreters through communicative interventions and the nuancing of their professional behaviour as their work intersects with political, social, and cultural conflicts in PSI settings.

This article is structured as follows. Since it does not propose to reprise well-established conceptualizations of interpreting through formal social justice collectives but aims instead to consider practices of dispersed activism, the article immediately introduces practice theory. In the remaining sections, the article explains the research context and methods, analyzing interpreters’ socially oriented practices in the United Kingdom’s public services. It concludes with a discussion of the study’s theoretical and practical implications.

2. Practice-based theoretical approach

Practice theories are a family of ontological orientations that take open-ended, orderly and materially mediated doings and sayings (“practices”) as central to understanding social and organizational phenomena (Nicolini, 2012). Socio-philosophical traditions – including Marxism, North American pragmatism and the work of Heidegger, Wittgenstein, Latour, Foucault, Bourdieu, and Giddens – are commonly identified as the intellectual grounds of practice theories. However, it is with the second generation of practice theorists – most notably Schatzki (2002), Reckwitz (2002) and Nicolini (2012) – that practice-based theories have “put concrete human activity – with blood, sweat, tears, and all – at the centre of the study of the production, reproduction, and change of social phenomena” (Nicolini & Monteiro, 2017, p. 2). Consequently, as opposed to the rational and utilitarian models of social action (such as those of Parsons and Durkheim), practice theorists locate the social in practices, not in the mind, discourse, individuals, or structures. Accordingly, the emphasis lies in investigating practice while still acknowledging that practitioners (human agents) serve as one of the valuable prisms through which practices can be appreciated.

While there is no single approach to practice, all the contemporary practice theorists view practices as organized activities. In the most quoted version, Schatzki (2002, p. 86) suggests that practices comprise discrete conceptual categories: “practical understandings” (know how); “rules” (instructions, directions, sanctions, etc.); “teleoaffective structures” (i.e., normativized goals and emotions), and “general understandings” (a broad category of collective concepts such as “nation” or diffuse cultural and political notions such as sustainability, ethnicity, or gender). Particularly relevant to our discussion are “teleoaffective structures” and “general understandings”. The former combine overarching goals that guide actions (teleo) with the emotional responses (affective) associated with these goals. In practice, they influence individuals’ perceptions, motivations, and behaviours, providing a sense of direction for engaging with one’s surroundings. For instance, shared goals such as social justice in a community evoke solidarity and commitment, reinforcing a collective identity and mode of practising towards meeting such goals. This emotional cohesion sustains practitioners’ norms and values, fostering a sense of connection and motivating their participation in the practice; in this way it perpetuates its normative framework. Moreover, given that practices are collectively acquired and executed, teleoaffective structures help individuals to engage in practices that foster shared responsibility by delineating standards of right and wrong (i.e., determining what is acceptable and what constitutes a transgression) (Nicolini & Monteiro, 2017). However, participation in practices does not entail blind adherence to rules: room exists for agency through initiative and creativity. For instance, codes of conduct represent part of PSIs’ normative compass; yet, as much research has demonstrated, a nuanced interplay exists – an evaluative space for interpreters to adapt their actions and impact (Skaaden, 2019; Valero-Garcés & Tipton, 2017).

In contrast, general understandings, as articulated by Schatzki (2002), refer to the shared or common knowledge that exists in a social group or community. These understandings encompass the collective expectations that guide individuals’ actions and interactions in a particular domain. Unlike teleoaffective structures, general understandings focus more broadly on the collective understandings that underpin social life; they serve as a backdrop against which practices unfold, providing an overarching framework for interpretation and action.

Practices always interlink with other practices (Nicolini, 2012; Schatzki, 2002; Shove et al., 2012), forming more or less harmonious configurations (Nicolini & Monteiro, 2017). These interrelations allow practices to coevolve, obstruct, or support one another, in this way generating asymmetries and inequalities and also giving or denying people the power to act and to think of themselves in certain ways (Nicolini, 2012, p. 6). For example, across a variety of settings (e.g., legal or healthcare contexts), providing a non-native X-language-speaking individual with an interpreter who lacks the cultural competence in or understanding of a particular dialect can perpetuate inequality. Moreover, misinterpretations may affect their ability to present their case, leading to unequal access to justice or to the provision of medical care. Concretely, a praxeological epistemology provides opportunities to interrogate from a particular “political” angle the PSI practices and their conjunction with the practices of the institutional settings in which they are located (see Ortner, 1984, p. 149).

As scholarship attests, there has been a growing interest in using this ontological approach in interpreting and translation studies. Drawing on practice theory, Olohan (2021) points to the socio-material complexities of commercial translation, shifting the focus from translation as a product to the social, bodily, and economic implications of performing translation. In the sphere of interpreting studies, Giustini (2019, 2021, 2023a, 2023b) has theorized about spoken-language interpreting and the traditional assumptions about the interpreters’ role (e.g., their invisible work) arising from a complex socio-material context in which habits, activities, and relationalities are arranged towards the market production and consumption of language labour vis-à-vis stakeholders. Moreover, Boéri and Giustini (2023, 2024) have developed a methodology of qualitative inquiry to account for the way interpreters, providers, and users negotiate cross-cultural and cross-linguistic discourses and actions in times of crisis. In centring patterns of development, change, and human cohabitation into practice, these studies drew attention to a powerful method of reframing translation and interpreting as socio-material organized activities. This is a crucial development, since it allows us to gauge the ways in which exchanges and mutually conditioning relationships – including inequalities, ideological clashes, competing narratives, and diverging institutional interests – are constituted in practice. In the case of PSI, this goes hand in hand with a series of related commitments, such as recalibrating understandings of interpreting practices and practitioners by questioning forms of knowledge and power and in the process fostering inclusive and nuanced perspectives.

2.1 PSI practices for social justice: political reparation and dispersed activities

Building on the previous section, this section elaborates on social justice-oriented endeavours in spoken-language PSI. In doing so, it is guided by Welch and Yates’ (2018, 2022) practice-based framework for dispersed collective activity, which is in turn rooted in Schatzki (2002).

Welch and Yates (2018) contend that practice-based theories have identified two main kinds of collective activities. These are groupings and bureaucratic organizations around which much research about social justice centres, as evinced in studies of consumption and sustainability (Welch & Warde, 2015). These collectives emerge from specific practices and their practitioners, encompassing examples such as consumer groups – for example, vegans (Twine, 2018) – communities affected by particular practices – for example, climate-change protesters (Nash et al., 2017) – and social movements exhibiting organizational qualities (Staggenborg, 2013). However, practice theories notably contribute to understanding a third type of social action – “dispersed collective activity” (Welch & Yates, 2018; 2022) – which this article leverages. Dispersed collective activity refers to the “ways in which the socially, spatially and temporally patterned character of practices and arrangements gives rise to aggregate effects” of social change, potentially leading to the formal organization, communication, or planning of activism (Welch & Yates, 2018, p. 298).

Moreover, Welch and Yates (2018, 2022) propose that dispersed collective activities are intertwined with general understandings and teleoaffective structures. This is because socially and justice-oriented action is collectively structured by diffused concepts such as the notions of political, gender, or language equality (Welch & Warde, 2015). General understandings straddle the boundary between practices and may exhibit affective aspects. They therefore play a central role in processes of identification with the ethos of social justice through identities, values and organizing concepts (such as “language access” or “non-discrimination”). Furthermore, general understandings guide the arrangement of teleoaffective structures, organizing the goals, orientations, and emotional engagements of individual practices. For example, a broader understanding of non-discrimination and language equality can permeate the teleoaffective structures of PSI, guiding practitioners to prioritize language rights and cultural sensitivity in their actions.

Finally, dispersed collective activity lacks formal or explicit coordination. Welch and Yates (2018) employed Melucci’s (1996) concept of a “latent network” to suggest that in dispersed collective activities individuals do not explicitly associate themselves with any formally organized entity. Instead, they typically engage in isolated acts of social justice by identifying with the relevant activity or practice. This conceptualization has distinctive implications for this article. Whereas PSIs may align strongly with the social ethos of their occupation, they may not necessarily identify with a highly structured collective endeavour, such as an organized social movement.

PSI is no stranger to dispersed collective activity, as is demonstrated in Giustini’s (2019) ethnographic study employing practice theory. This research studied interpreters in Japan who served as intermediaries between national and international institutions, on the one hand, and the local community, on the other, in the aftermath of the 2011 nuclear disaster accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant of Ōkuma and Futaba, caused by the tsunami which followed the Tōhoku earthquake. In a departure from their customary rule-bound normatively neutral roles, these interpreters engaged with the teleoaffective dimensions of their job in that disaster-stricken environment, operating within a framework of “reparative politics” (Giustini, 2019, p. 198). Through their linguistic and affective interventions, the interpreters offered the local community an opportunity to influence the situation, and offered institutions the opportunity to reconsider their aid role. Therefore, in responding to the ethical imperative of facilitating communication for the Fukushima prefecture’s residents and navigating the pervasive feelings of despair and dislocation, the interpreters effectively delivered a form of social justice. They did so by using the politics of language to mediate and to magnify the socio-communicative encounter between the local population and the institutions. Importantly, and despite their efforts lacking formal coordination as a social movement, all the interpreters in the study shared a common sense of personal and professional alignment with unstructured forms of social activism against nuclear energy power. Collectively, these dynamics formed the core of the political dimension of their work, exemplifying how latent networks, though rooted in dispersed activity, can coalesce around ad-hoc objectives, in this way enhancing their capacity to influence inequality outcomes (Welch & Yates, 2018).

In what follows, the article harnesses the analytical potential of a practice-based approach to explore non-organized dispersed modes of social activism among United Kingdom-based PSIs. In the use of “non-organized dispersed forms of activism” this article refers to interpreters’ situated activities[i] that are aimed at embracing Otherness, social justice, and political restitution. As I show, these activities are often manifested in cultural–linguistic exchanges and are frequently directed at containing the inequalities that are emerging in institutional settings. Furthermore, in keeping with a practice-oriented sensitivity, I define “Otherness” as doings and sayings (actions and discourses), thus a practice (othering). I borrow the conceptual contribution of Spivak’s (1988) postcolonial approach, which defines “othering” as the ways we frame and marginalize groups as being essentially different from a presumed “norm”. Such othering practices are used to justify exclusion, discrimination, or even violence against marginalized groups, whereas practices of embracing Otherness emphasize inclusivity, empathy, and recognition of the value and diversity of all individuals and communities. Adapted to PSI, I view othering as the translation of hegemonic discourses into everyday sociocultural and linguistic practices, so that they enter the habitual spaces of institutional experience inhabited by providers, users, and interpreters. Importantly, positioning othering as a practice implies recognizing the potential of PSIs’ dispersed activism (embracing Otherness) to contain and fight power dynamics and inequalities, since connections between practices are at the heart of change and the defiance of systemic injustice (Boéri & Giustini, 2023; see also Nicolini & Monteiro, 2017; Shove et al., 2012).

3. Research Setting and Methodology

3.1 Research context

Interpreting in the United Kingdom is vital for effective communication in public service contexts, such as legal, healthcare, and social welfare. Public sector organizations such as the National Health Service (NHS) and the justice system typically commission PSI through contracts or centralized language service agreements which manage the supply of interpreters. However, budget constraints and government funding cuts often limit access to interpreting services, creating barriers for those in need. There are also manifestations of the inverse correlation that exists between a public service sector or organization’s capacity to pay for professional interpreting services and the volume of non-professional activity taking place in their environment. The shortage of economic resources has also led to an important drive towards the emergence of volunteer interpreters, some of whom have no training in the field. For example, it has become increasingly common in institutional settings (e.g., healthcare, judicial and educational) for users to rely on family members or friends as mediators (Pérez-González & Susam-Saraeva, 2012). Additionally, despite the existence of the National Register of Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI, a body overseeing professional accreditation), the independent and voluntary regulatory nature of this organization, coupled with absence of national standards for assessing language skills, interpreting techniques, and adherence to a code of conduct has implications for the homogenous upholding of interpretation quality. Consequently, PSI faces ongoing pressure arising from contract-driven work, ad-hoc provision of services (Hale, 2007) and insufficient public recognition, all of which result in low prestige being attached to PSIs as an undervalued labour force (Mikkelson, 1996).

In the linguistically diverse United Kingdom, where more than 300 languages are spoken, the potential for discrimination, power imbalances, and cultural barriers is significant among individuals with limited English proficiency when dealing with public service providers (Giustini, 2020). These disparities are compounded by prevalent inequalities in income, education, health, and ethnicity across the country (cf. Office for National Statistics, 2023). As a result, PSIs often work alongside vulnerable or marginalized communities. It is worth stressing that in PSI, one relevant issue is that interpreters are often members of the “guest culture” (Gavioli & Baraldi, 2011), that is, they are part of the same communities they work for. The overlap between their professional practices and their communities’ practices often means that interpreters suffer from conflicts of role relating to issues of advocacy and cooperation with the other interlocutors in the communicative event. Frequently, they have to re-negotiate their position in an interaction (Pöllabauer, 2004), with implications for some of their interpreting and intercultural mediation decisions aimed at resolving power imbalances (Boéri & Giustini, 2023). These imbalances are rooted in language inequalities embedded in institutional power structures which permeate welfare settings. These settings are governed by the legal mandates and authority of public service professionals to assess the private lives and practices of their clients (Gustafsson, 2023).

3.2 Methods

To examine justice-oriented practices of dispersed collective activity in PSI, this study relied upon a qualitative dataset derived from 34 in-depth semi-structured interviews with PSIs. The interviews were conducted within the frame of a wider ethnographic project of interpreting in the United Kingdom (carried out in 2014–2019, followed up in 2020–2021).

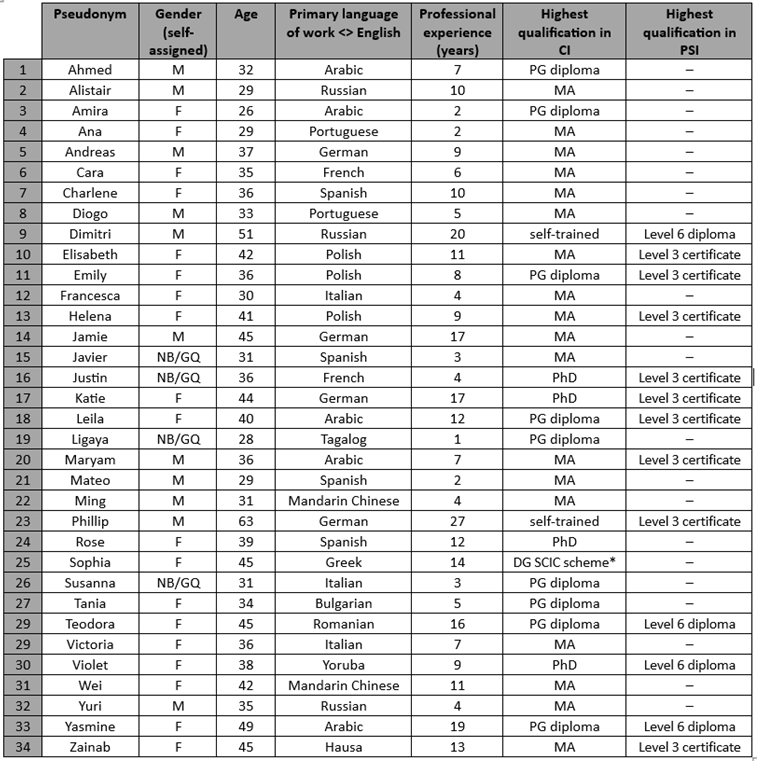

The interpreters interviewed had extensive experience in public service settings (court/legal, asylum, healthcare, and social work). They were also active conference interpreters. All of them were self-employed (freelancers). Their age spanned from 26 to 63, with a median average age of 42 years. Their professional experience ranged from one to 27 years, with a median average of nine years in the interpreting sector overall. Reflecting the multilingual nature of the United Kingdom and its public services, the interpreters’ language combinations were varied; they always included English, paired with either Arabic, Bulgarian, Chinese, French, German, Greek, Hausa, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, or Yoruba. Of the 34 informants, 19 self-identified as female, 11 as male, and four as non-binary/queer.

The research participants’ qualifications reflect the homogeneous landscape of PSI in the United Kingdom with regard to education and minimum benchmark criteria for assessing interpreting skills in its settings. Most of the interpreters had completed specialized higher education in conference interpreting (CI); two senior interpreters were self-trained; one had completed an institutional training scheme offered by the DG SCIC, which is no longer active. However, half of the sample had not pursued additional qualifications in PSI to operate in fields such as healthcare, law, or police. The other half had instead completed a higher level of qualification in PSI, either through the Level 3 Certificate or the Level 6 Diploma. The former is an entry-level qualification offered by bodies such as metropolitan borough councils covering various aspects of interpreting and assignment preparation in English and other languages. The latter is equivalent to a degree and covers topical specializations (e.g., law) and more advanced linguistic and interpreting skills. It is offered by bodies such as the Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL). As Section 4.1 details, the participants’ dual role as conference and public service interpreters and their qualifications played a significant role. In fact, they tended to articulate their understanding of PSI through the lens of CI, a stance that had implications for data analysis and interpretation, especially regarding the participants’ discourses and experiences of dispersed activism. Full socio-demographic information is available in Table 1. Inizio modulo.

Informant recruitment proceeded through a mix of stratified purposeful and snowball sampling to non-randomly select United Kingdom-based informants who could provide in-depth insights into interpreting practices in the national context. It should be noted that while this sampling method supported the primary focus of the original study on CI, the inclusion of informants with experience in both CI and PSI emerged organically during the sampling process. This occurrence reflects the often-intertwined nature of CI and PSI in the private interpreting market in the United Kingdom. Institutional ethical approval by the University of Manchester was sought and granted. Social research ethical guidelines were followed, including gaining informed consent and guaranteeing anonymity to ensure privacy and confidentiality.

Table 1

Socio-demographics of informants

Legend: F = female, M = male, NB/GQ = non-binary/genderqueer, PG = postgraduate, * no longer active

During the interviews, which lasted about 80 minutes and were audio-recorded, the interpreters were asked to share reflexive accounts of their professional practice that they perceived as revelatory of issues such as inequality, power imbalances, prejudice, and discrimination. The interviews were fully transcribed and coded using the NVivo software through Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA). An iterative abductive process was used to analyse the data, alternating inductive and deductive coding as in the tradition of interpretive and practice-based scholarship (Yanow & Schwartz-Shea, 2014). No set analytical categories were identified prior to entry into the field, although the research design used a practice-based approach as a sensitising frame. Raw data were first developed into conceptual codes and systematically classified to identify occurrences and meanings. Codes were then grouped inductively into broader categories and themes, which identified core consistencies and controversies of equality, inclusion, and justice in the PSIs’ practices. At this point, the analysis proceeded deductively, starting by organizing the themes to chime with a praxeological sensitivity. For the scope of this article, themes were then scrutinized according to the main elements of practice (e.g., “general understandings”, “teleoaffective structures”) that spoke of dispersed collective activities.

4. Findings

This section shows how PSIs contribute to linguistic and social justice through their interpreting practices. It conceptualizes these as dispersed collective activities with the potential to empower interpreters, deal with institutional language policy failures, and combat oppressive frameworks in public services while centring minoritized voices.

4.1 Activist characterization of PSI practices

Importantly, in discussing their roles in PSI and CI, the interpreters noted that their work in public service allowed them to refocus on social justice. Tania (34), for instance, reported that she[ii] balances conference and public service work in order to steer interpreting against societal and institutional oppression:

What I’m up to is, I work with mainstream clients, such as multinational corporations and policy-making institutions, but I also work a lot in community settings with marginalized communities, and I do pro-bono interpreting gigs for NGOs helping migrants and asylum seekers. I try to tip the scales a bit because otherwise, we end up serving the oppressors day in, day out.

Using a rhetoric of defiance and intervention that fights the oppressor and its ramified power, interpreters such as Tania did not conceive pro bono and public service work as devaluing their labour or as inferior to their work in conference settings. Rather, specialist knowledge and interlingual transfer operations in the community settings were framed as activist instruments for upturning inequality, which were sometimes subtly paired with the clients and the institutions that the interpreters served in conference settings. This balancing act linked the teleological goal of language access, upheld in both CI and PSI, to broader social change efforts, which the interpreters felt had more impact and importance in PSI settings.

Furthermore, several interpreters reported that their activism meant labouring through language to affect institutional encounters positively, taking advantage of the proximity between interpreters and other participants. In discussing PSI and CI again, Helena (41) and Teodora (45) highlighted their different dimensions of expertise and impact:

People may not have the same perception of the job according to whether it’s PSI or CI, they believe the setting is different, the skills are different. … In terms of practical, technical skills I think instead they’re the same even if they’re differently used according to the setting. … Rather I think the dynamics are really important, because you are so close to the person and the setting, you see exactly what’s happening in PSI. … Your work has an impact. It’s not necessarily the case in CI. In PSI, you just know you’re helping someone personally to have their needs met. To me it means supporting a good cause. (Helena)

In CI, we want to produce good quality interpreting, but I’m not sure we are expected to be impactful. PSI is different. I think that PS interpreters make such a difference in people’s life, if you’re working in a medical setting or in immigration and giving voice to people there, is a massive deal … Probably in PSI we have more the feeling that we’re doing something to help, doing some good in the world, especially if the setting is aligned to our ideals and values. (Teodora)

Whereas CI is expected to establish communication between so-called experts, PSI becomes the voice of the migrant, the minority speaker, the oppressed, or the ill, among many others. When interpreting for the “subaltern” (see Spivak, 1988), who are speechless because they are either incapable of speaking for themselves or because they are denied the right to speak (Bahadır, 2010), the interpreters experienced their service provision in PSI as teleologically superior to that in CI. They not only identified public service settings as loci where mutual understanding is more vital than CI; they also identified their labour as capable of defying othering practices, being more invested in promoting justice and fairness.

Furthermore, the teleoaffective significance of interpreters’ communicative contributions in public services is complemented by considering technical proficiency and interpreting expertise as intrinsic qualities associated with the virtuous pursuit of their professional calling. This perspective, which emphasizes a commitment to the wider goals of the profession, reinforces interpreters’ shared sense of dedication to PSI as a means of personal activism, aligning with the broader notion of “supporting a good cause”. Although highly individualized (“you just know you’re helping someone personally”), the interpreters’ communicative practices aggregate as dispersed activism.

4.2 Of bodily, affective, and material resonances in interpreters’ dispersed activism

As anticipated in Section 2, practices are organized through motivational knowledge and normativized emotions: the affect- and goal-oriented axes of activity. Public service settings, including hospitals, government offices, and social welfare organizations, cater to communities’ needs and often become focal points where individuals experience strong emotions, including through interpreted interactions. Many interpreters in this study frequently empathized with the setting, the situation, and the users. This state worked to enhance communication and understanding, but it also brought with it emotional and bodily challenges. Katie (44) and Charlene (36), both highly experienced in legal and medical interpreting, described their engagement with the affective and embodied aspects of each job and the individuals involved:

PS interpreters need to deal with very emotional situations … we deal with such dramatic things that it affects me, I often feel sick in my stomach and drained afterwards … and you know legal and asylum settings can be pretty gruesome, and there’s much interpersonal contact, and yet you’re expected – you must – never lose focus. (Katie)

The emotional commitment is very deep in PSI. Imagine being with your client in a medical setting which could be very traumatizing to you … once I fainted seeing a lot of blood [laughs]. Or mental health, I do a lot of mental health and that’s pretty tough. … In my voice I learned to hide if I’m a bit stressed or scared, so I can appear calm generally and I try not let my emotions rule me when I’m interpreting. (Charlene)

Whereas emotional management was partly internalized as an ethical principle (“I do not let my emotions rule me when I’m interpreting”), it seldom coincided with uncritical tenets of neutrality in PSI. If only with their voice, the interpreters channelled their activism as an intimate communicative relationship, which took a toll on both the body and the mind. Here we face a paradox: on the one hand, as also dispelled by Metzger (1999) and Angelelli (2004) among others, the undeniable bodily presence of the interpreter wipes away the myth of the neutral, apolitical, unemotional, and therefore disengaged interpreter. On the other hand, we witness the emotional expansion of the interpreter as a tangible, audible, and feeling entity whose body cannot be conveniently forgotten in uncomfortable situations – from blood tests to mental healthcare consultations. Indeed, the interpreters construed both bodily effects and emotional resonance as tools that multiplied the impact of interpreting. This teleoaffective extension often worked in tandem with general understandings of equality and well-being inscribed in settings such as mental healthcare. Consider, for instance, Cara’s (35) story. She was actively involved in community initiatives in Northern England:

I’m a big advocate for mental health and well-being; I work a lot in these sectors. I had a client who I used to go and see in [neighbourhood] in [city], for mental health. She had ... most of my clients are psychologically damaged, coming from African countries where they have seen war, and torture, rape and everything. I used to see that woman quite regularly and when she was better it made me happy because I could see a progress; when she wasn’t, I was very sad. Professionally, it was nice to have a continuity with her, and have an impact through the job.

As Cara underscores, interpreting practices are also emotional–communicative experiences. Her account highlights in particular the significant role of teleoaffectivity in shaping interpreting practice. The joy, but also the sadness, she experiences when witnessing her client’s trajectory reflects a deep sense of emotional investment derived from contributing to the Other’s communicative needs – highlighting the affective dimension of her work. Conversely, her account illustrates how emotions can drive interpreters’ practice, in this way showing how interpreting work can be teleologically motivated by bodily and sensory resonances. Taken together, the teleological and affective components indicate how often interpreters transcend their role boundaries to exercise agency and contribute meaningfully to the well-being and progress of those they serve. This, in turn, accounts for the “politics of interpreting affect” (Giustini, 2019) which refers to the recognition that interpreting practices are not solely socio-linguistic experiences, but are deeply entangled with the emotional and the bodily-material.

The material dimension of interpreters’ dispersed activism was particularly vivid in their experiences of the criminal justice system, as Justin (36) recalled. As part of precautionary and ethical measures, interpreters in police and prison settings in the United Kingdom are required to abide by security procedures and formalized guidelines, such as the Code of Conduct of The Association of Police and Court Interpreters (APCI). These guidelines include refraining from activities which pose a significant risk of a conflict of interest with the role of an official interpreter and directing interpreters to assist all parties (e.g., convicts, witnesses, defendants, prosecutors, solicitors) by equally upholding impartiality as part of effective communication (APCI, 2023). However, ethical conflicts may arise in the performance of professional conduct. For Justin, this was tied to the constrained sense of humanity they experienced working in correctional facilities:

I remember one case with a solicitor [provider], the guy [user], he was a young undocumented inmate from North Africa, kept on talking about missing to eat so-and-so biscuits in prison, he went on and on that he didn’t have the money to buy items from the prison shop, and the solicitor just turned around, he couldn’t care less. But he was really going on and on about it, and although I was still interpreting it exactly the way he said, I kept wondering, maybe we can see if he has someone that can send some little money? I did approach the solicitor at the end to ask. … Yes, I overstepped my role. The issue of the role of the interpreter is a very thorny issue [embarrassed laughter] but there was something in that very basic, very human request, that I could just not turn my back.

In the United Kingdom, prison regulations restrict visitors from bringing food to inmates, relying on institutional facilities such as the prison canteen for meals. Inmates can make purchases from the canteen using their own funds or allowances. Justin’s suggestion aligns with this procedure but contradicts normativity. They feel compelled by their professional role to uphold the basic human rights of the inmate. The characterization of the inmate as speechless – that is, lacking political representation in the encounter were it not for the interpreter’s intervention – raises significant questions, though: Can an interpreter arrogate the role of spokesperson for the “subaltern” to themselves? Can they claim to be an advocate of and transfer the needs of the “speechless”? Inside the correctional facility, Justin viewed the solicitor as the oppressor and the economically dominant figure, considering the inmate’s speechlessness as a metaphor for material deprivation. Their intervention highlights how dispersed collective activities, such as supporting an inmate’s request as part of the facility’s procedures, intertwine with the material (biscuits, prison, bodily needs), economic (money), social (relations with involved individuals), and discursive (spoken words) dimensions, which in turn are connected to the teleoaffective structures of both the correctional facility practices and the interpreting practices.

Teleoaffective structures may establish normative principles such as interpreter impartiality, particularly in specific settings (e.g., the criminal justice system), since they intersect with institutionalized and broader general understandings (e.g., state authority, the rule of law). Justin’s intervention revealed a conflict between expected behaviour and actual practice, and it at once challenged both the alleged teleological and normative structures of interpreting and also the prison’s institutionalized power dynamics. However, it is essential to acknowledge that solicitors operating in such environments often face overwhelming caseloads and may either be desensitized to individual pleas or be reluctant to step out of their role to accommodate additional requests. This reality challenges the expectation of consistent institutional support and fairness in every instance. In the case highlighted, the interpreter tries to act in between ethical imperatives and institutional constraints in the criminal justice system to deal with perceived systemic inequalities – that is, the additional privations that minoritized language speakers in these environments can be subject to due to their limited ability to communicate. On this occasion, it is the actions of the interpreter that speak of reparation rather than those of the solicitor.

4.3 Managing language politics

Finally, the path to social justice passed for many interpreters through the management of language politics, that is, the regulation of institutionalized communication through the social and professional functions of interpreting (cf. Giustini, 2020). PSI is ascribed to supporting vulnerable communities, but the lived reality is not as straightforward, as Maryam (36), a Syrian interpreter, indicated:

Since long ago I was interested in interpreting, because … I always had an interest in language and politics … since when I was at home in Syria. In PSI my most common problem is how to handle the situation, how to intervene within the limits of your role. Some people from the Arab world – I work with the Syrian, Iraqi language varieties of the diaspora – would come here and feel in an alien environment. They may feel homesick. They may feel weird about the whole interpreting experience, in a country where they don’t know the language, and often talking about intimate topics … You deal with immigration cases, refugee cases, and they [government authorities] may need to decide whether they deport this person. That, and because of past and present practices of governments … they [users] are apprehensive.

This is a telling illustration of how the politics of language intersects with experiences of diaspora, alienation, and displacement. Maryam’s attention to users’ experiential histories and reactions aims at minimizing their hardships in dealing with interpreting and institutional processes. Furthermore, her discourse highlights that rights to language access are not only an entitlement to language services, but part of the wider question of the ethical responsibility states have to asylum-seekers, refugees, and economic migrants. The mention of government practices and their potential negative outcomes (“whether they deport this person”) underlines that interpreting practices cannot be separated from institutional dynamics. Yet, Maryam questions the extent of her professional interventions (“within the limits of your role”) and therefore the extent to which interpreters can influence social change. This point was echoed by Rose (39), who had more than ten years’ experience in legal and asylum settings:

I view interactions quite realistically and if I need to have a side conversation to clarify something, or if I need to put somebody in the frame and remind them, we haven’t covered this or that person wouldn’t know what that is, I wouldn’t have a problem to say this as an interpreter, because I am thinking all the time, how do I establish the level of play field? And sometimes service providers overlook the lack of general knowledge of our assistance work from the part of the asylum seeker or the refugee, and I feel it’s important to give a bit of context. … Particularly in asylum cases is very common as I found out, you tell them “I’m the interpreter”, and they may reply “In my country there’s the war, and so and so” so I learned, people who are seeking asylum think, “Oh this is my only chance, I need to get my story out to the authorities”. … So often I intervene and help with the dynamics because I want to facilitate the asylum granting.

When confronted with the erosion of human rights, the interpreter’s third voice claims to replace and (re-)create the voice of the Other to facilitate the performance of solidarity in the institutional space. In Rose’s illustration, institutions are not necessarily the site of orderly practices capable of providing adequate service to marginalized communities. Rather, they are the site of othering practices, and can be complicit in silencing the Other and in gatekeeping knowledge. This brings interpreters to perform actions such as intervening in the interaction and clarifying institutional processes. Through these actions the interpreters adapted to the open-ended character of practices, taking advantage of their scope for initiative. In the excerpt, Rose positions herself as a co-negotiator of the asylum-seeking practice, as evidenced by her emphasis on establishing a level of “play field” (sic). This also means that the notion of the interpreter as an “apolitical” agent who merely facilitates language access is effectively replaced by the interpreter who becomes an instrument of (or against) the politics of institutional decisions. Whether this normative expansion of the interpreter’s professional responsibilities is ethical is a question that does not solve issues of positioning but, rather, magnifies it. In other words, as interpreting practices expand beyond linguistic mediation to include more activist considerations and broader professional roles, issues of positioning (such as power dynamics, cultural biases, or subjective interpretations) are not necessarily resolved. Whereas interpreters are expected to adhere to ethical standards, these expanded responsibilities (that interpreters decide to take upon themselves) can exacerbate the challenges of navigating their position in interactions.

Several interpreters engaged in such norm-bending actions, which grounded their dispersed practices of activism. Violet (38) and Emily (36), who specialized in medical and social services, extended their activism towards calling out institutional practices and actors:

I interpret for people in healthcare, like asylum seekers and refugees. I often see the GP [general practitioner] is not even remotely interested or takes the time to find what is wrong with that person. I’ve been with users and a GP who hasn’t even looked them in the eye, who prescribed medication without even asking, do you have any allergy, or are you pregnant? In these cases, I always call the medical staff out. Maybe it’s too much criticism from me, but … there is really a dismissive attitude towards this people. [Violet]

Interpreting practices here mesh with the intersectional character of inequality (according to gender, race, nationality, and health condition) and function as an instrument with which to counter discrimination. Violet’s actions prevent medical negligence and focus on social injustice stemming from institutional lack of interest in vulnerable user categories – an activist strategy also implemented by Emily:

One time I couldn’t stop myself … it was a repeated assignment for a pregnant woman, she was an alcoholic, very unstable environment, and the social services wanted to take away the older child from her. It was very draining. Once I was on my own dealing with twenty different professionals that were there to assess her case … social workers, police, and so on, they came across as very oppositional. This lady felt really challenged and scared. Until she hit me. … So the social services told me, if you want to press charges with the police, they’re going to arrest her. And I said, “I’m fine, but … clearly we’re not doing anything to help her.” I was so frustrated. We had a chat about what happened afterwards and they recognized that their behaviour perhaps was not the best given the circumstances. [Emily]

The user openly identifies the interpreter with the institution (social and children’s services), its practices (case assessment) and its constituency (social workers, the police). While the institution proceeds equally to identify the interpreter among its constituency by proposing that Emily press charges against the user, she takes responsibility for such association and questions the validity of institutional practices, in which she includes both herself and the interpreting practices (“we’re not doing anything to help her”).

Finally, interpreters’ dispersed forms of activism were not limited to the interpreted events but transcended their boundaries. Consider Wei’s (42) insistence on agencies and organizations that should be adequately supporting interpreters’ work:

Often the problem for PSI is actually that you don’t have anything to prepare … I remember once it ended up being with a psychiatric nurse, and I said, well, I would have liked briefing because we ended up going to a patient’s house for a check up, and I didn’t know that the person had mental health issues. At first she was saying things that didn’t make any sense, I thought, what is she talking about, and then I realized she had mental health issues. They should have told me. It’s not only about polishing your terminology. It’s about respect for the client, knowing how to deal with them, make them feel “my role can be trusted, you don’t need to fear me”. I told the organization representative and the agency afterwards, either you give me an idea of the assignment next time or I won’t engage in unhelpful ways of practising my profession. After that, now they always give me details.

5. Concluding discussion

In responding to the research questions, the article drew on Schatzki’s (2002) account of practice as a starting point for a practice-based conceptualization of interpreters’ social justice-oriented actions in public service settings. Bridging this account with Welch and Yates’ (2018, 2022) understanding of activism as grounded in the teleoaffective and general understandings of practices allowed this article to frame PSIs’ enactments as dispersed forms of activism. This conceptualization made it possible to explain how spoken-language interpreters’ activism, despite its fragmented, non-formalized, and non-collective nature, could generate a space of resistance against inequality and power asymmetries in the interpreted encounters and the institutions where these occur. This space of resistance was enacted through and by the politics of language. This refers to the dynamic interplay between language, interpreters’ objectives, and their emotionally driven behaviours (goal- and affective-oriented actions) aimed at insisting on fairness being imposed on unsustainable institutional practices that could otherwise neglect users’ needs and rights.

The findings reveal that resistance to oppression by the powerful and the institutional call for practices of resistance from the interpreters if they are not to succumb to the challenges involved in simultaneously representing and mediating the speech of the Other in public service settings. It is in this space of practising that dispersed forms of activism emerge – the loci where the interpreters who feel uneasy vis-à-vis mechanisms of discrimination decide to act. Those who act take on the emotional, bodily, material, ethical, and professional burdens of their articulations. Amplifying the voice of the unheard and aggregating the effects of fragmented yet multiple socio-communicative interventions, interpreters took the first step towards developing social justice that was grounded in activism – however dispersed.

This work contributes to the literature on PSI and social justice in three ways. First, through the onto-epistemological prism of practices, it frames activism in PSI as ad-hoc yet pervasive equity-driven initiatives that concretize social justice in public services, spoken language, and civil society. This theoretical groundwork complements existing conceptualizations of activist interpreters’ collective experiences (Bancroft, 2015; Boéri, 2012; Boéri & Delgado-Luchner, 2020; Monzó-Nebot & Mellinger, 2022; Prunč, 2012; Wallace & Monzó-Nebot, 2019). In particular, it adds novel insights to the intersecting perspectives of interpreters who navigate both CI and PSI settings, enriching scholarly understanding of the motivations and values that drive interpreters in their practices. This finding highlights the ways the interpreters often drew on and compared their experiences in CI when reflecting on their PSI work. They contrasted the two according to skills, ethos, and justice orientation, depicting PSI in a very positive light across these dimensions. This understanding challenges the common narratives that portray PSI as less professionally fulfilling than CI and illustrates the way in which interpreters can perceive their PSI work as being equally intellectually demanding and more socially impactful.

Second, the study has shed light on the ways dispersed activist practices intersect with teleoaffective and general understandings of fairness and equity, challenging the notion of interpreters as being apolitical and impartial (cf. Skaaden, 2019; Valero-Garcés & Tipton, 2017; see also Giustini, 2019). Instead, it highlights their role as being embedded in and influencing institutional settings. This advances our understanding of the norm-related complexities faced by interpreters in amplifying marginalized voices (Boéri & Giustini, 2023, 2024) and acting as advocates of the voiceless in public services (Bahadır, 2010).

Finally, the study indicates that PSIs’ social justice practices (within the frame of spoken language), along with their bodily, affective, and material dimensions, serve as a tool for managing the politics of language in public services. It presents PSIs’ social and communicative actions as teleologically oriented towards localized social change. In essence, the article positions PSIs’ dispersed activist practices as a form of political reparation – interpreters’ contributions aimed at challenging existing unsustainability in systemic structures that perpetuate vulnerability in social and public domains. Overall, the informants’ experiences point to a “latent network” (Melucci, 1996; Welch & Yates, 2018), since their actions are grounded in a shared professional identity and common beliefs, values, and goals. These reflect an overall commitment to creating equitable conditions for underprivileged users in public services. While such a latent network may not have a formal organizational structure, interpreters’ informal, repeated actions collectively contribute to broader efforts to improve language access, challenge discrimination, and lead to vulnerable communities’ rights being championed.

The study has highlighted the implications for sustainable PSI practices and policies. It calls on institutions and professional associations to afford better recognition to the dynamics at play between interpreting and public service actors, practices, and their sites of enactment. Careful empirical work is needed to explore complex power asymmetries and in so doing identify where more effective and inclusive measures should be directed to advance the goals of social justice in PSI. Taking stock of those interpreters’ interventionist experiences highlighted in this article could result in practices of non-discrimination being advanced through improved and formally recognized institutional policies across public services. In other words, the aggregate effects of interpreters’ dispersed activism could result, as Welch and Yates (2018) remark, in more organized and planned forms of communication and user protection.

Of course, the generalizability of the results and their implications is limited by the qualitative nature of the study and by its sampling strategies. However, whereas the sample may not fully represent the entire population of PSIs in the United Kingdom, the approach ensured a nuanced representation of diverse perspectives and experiences. By capturing a range of voices in each stratum, the findings’ implications could be enhanced by their application to similar individuals or contexts beyond the selected sample (Suri, 2011). Future PSI research could, for instance, explore both dispersed and organized language-based activism in public services, in addition to attending to the experiences not only of spoken, but also of sign-language interpreters. Overall, examining the ways in which PSIs form collective identities and engage in social and political movements across public-facing contexts can equip us to understand better PSI practices’ role in promoting social justice and equity.

References

S. (2013). The cultural politics of emotion. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203700372

Angelelli, C. V. (2004). Medical interpreting and cross-cultural communication. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511486616

Bancroft, M. A. (2015). A profession rooted in social justice. In E. Mikkelson & R. Jourdenais, (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of interpreting (pp. 217–235). Routledge.

Bahadır, Ş. (2010). The task of the interpreter in the struggle of the other for empowerment: Mythical utopia or sine qua non of professionalism? Translation and Interpreting Studies, 5(1), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.5.1.08bah

Baker, M. (2013). Translation as an alternative space for political action. Social Movement Studies, 12(1), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2012.685624

Baldo, M., Evans, J., & Guo, T. (2021). Introduction: Translation and LGBT+/queer activism. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 16(2), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.00051.int

Boéri, J. (2012). Translation/interpreting politics and praxis: The impact of political principles on Babels’ interpreting practice. The Translator, 18(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799511

Boéri, J. (2022). Steering ethics toward social justice: A model for a meta-ethics of interpreting. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 18(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.20070.boe

Boéri, J., & Delgado-Luchner, C. (2020). Ethics of activist translation and interpreting. In K. Koskinen & N. K. Pokorn (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and ethics (pp. 245–261). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003127970-19

Doerr, N. (2018). Political translation: How social movement democracies survive. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108355087

Federici, F. M. (2020). Translation in contexts of crisis. In E. Bielsa & D. Kapsakis (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and globalization (pp. 176–189). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003121848-15

Gavioli, L., & Baraldi, C. (2011). Interpreter-mediated interaction in healthcare and legal settings: Talk organization, context and the achievement of intercultural communication. Interpreting, 13(2), 205–233. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.2.03gav

Giustini, D. (2019). “It’s not just words, it’s the feeling, the passion, the emotions”: An ethnography of affect in interpreters’ practices in contemporary Japan. Asian Anthropology, 18(3), 186–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/1683478X.2019.1632546

Giustini, D. (2020). Interpreting the COVID-19 crisis. Everyday Society: British Sociological Association. https://es.britsoc.co.uk/interpreting-the-covid-19-crisis/

Giustini, D. (2021). “The whole thing is really managing crisis”: Practice theory insights into interpreters’ work experiences of success and failure. The British Journal of Sociology, 72(4), 1077–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12843

Giustini, D. (2023a). Embedded strangers in one’s own job? Freelance interpreters’ invisible work: A practice theory approach. Work, Employment and Society, 37(4), 952–971. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211059351

Giustini, D. (2023b). ‘They wouldn’t mind pushing people off the bus’: Exploring power in practice theory through the work of simultaneous interpreters. Sociological Research Online, 28(2), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/13607804211055489

Gustafsson, K. (2023). The ambiguity of interpreting. Ethnographic interviews with public service interpreters. In L. Gavioli & C. Wadensjö (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of public service interpreting (pp. 32–45). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429298202-4

Hale, S. (2007). Community interpreting. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230593442

Inghilleri, M. (2007). National sovereignty versus universal rights: Interpreting justice in a global context. Social Semiotics, 17(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330701311488

Kerremans, K., De Ryck, L. P., De Tobel, V., Janssens, R., Rillof, P., & Scheppers, M. (2018). Bridging the communication gap in multilingual service encounters: A Brussels case study. The European Legacy, 23(7–8), 757–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/10848770.2018.1492811

Melucci, A. (1996). Challenging codes: Collective action in the information age. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511520891

Metzger, M. (1999). Sign language interpreting: Deconstructing the myth of neutrality. Gallaudet University Press.

Mikkelson, H. (1996). Community interpreting: An emerging profession. Interpreting, 1(1), 125–129. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.1.1.08mik

Monzó-Nebot, E. M., & Mellinger, C. D. (2022). Language policies for social justice—Translation, interpreting, and access. Just: Journal of Language Rights & Minorities, 1(2), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.7203/Just.1.25367

Nash, N., Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S., Hargreaves, T., Poortinga, W., Thomas, G., Sautkina, E., & Xenias, D. (2017). Climate‐relevant behavioral spillover and the potential contribution of social practice theory. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 8(6), e481. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.481

Napier, J., Skinner, R., Adam, R., Stone, C., Pratt, S., Hinton, D. P., & Obasi, C. (2022). Representation and diversity in the sign language translation and interpreting profession in the United Kingdom. Interpreting and Society: A Interdisciplinary Journal, 2(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/27523810221127596

Nicolini, D. (2012). Practice theory, work, and organization: An introduction. Oxford University Press.

Nicolini, D., & Monteiro, P. (2017). The practice approach: For a praxeology of organisational and management studies. In A. Langley & H. Tsoukas (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of process organization studies (pp. 110–126). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957954.n7

Nordberg, C., & Kara, H. (2022). Unfolding occupational boundary work: Public service interpreting in social services for structurally vulnerable migrant populations in Finland. Just. Journal of Language Rights & Minorities, 1(1-2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.7203/Just.1.25002

Office for National Statistics. (2023). People, population and community. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity

Olohan, M. (2021). Translation and practice theory. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315514772

Ortner, S. (1984). Theory in anthropology since the sixties. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 26(1), 126–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500010811

Pérez-González, L., & Susam-Saraeva, Ş. (2012). Non-professionals translating and interpreting: Participatory and engaged perspectives. The Translator, 18(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799506

Pöllabauer, S. (2004). Interpreting in asylum hearings: Issues of role, responsibility and power. Interpreting, 6(2), 143–180. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.6.2.03pol

Prunč, E. (2012). Rights, realities and responsibilities in community interpreting. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 17, 1–12. http://hdl.handle.net/10077/8539

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. Penn State University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780271023717

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446250655

Skaaden, H. (2019). Invisible or invincible?: Professional integrity, ethics, and voice in public service interpreting. Perspectives, 27(5), 704–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018.1536725

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). MacMillan.

Staggenborg, S. (2013). Bureaucratization and social movements. In D.A. Snow, D. della Porta, D. McAdam, & B. Klandermans (Eds.), The Wiley‐Blackwell encyclopedia of social and political movements (pp. 1–4). Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm018

Suri, H. (2011). Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal, 11(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ1102063

The Association of Police and Court Interpreters (APCI). (2023). Code of conduct. https://apciinterpreters.org.uk/about-us/code-of-conduct/

Tiselius, E. (2021). Conference and community interpreting. In M. Albl-Mikasa & E. Tiselius (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of conference interpreting (pp. 19–22). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429297878-6

Twine, R. (2018). Materially constituting a sustainable food transition: The case of vegan eating practice. Sociology, 52(1), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517726647

Valero-Garcés, C., & Tipton, R. (2017). Ideology, ethics and policy development in public service interpreting and translation. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783097531

Wallace, M., & Monzó-Nebot, E. M. (2019). La traducció i la interpretació jurídiques en els serveis públics: Definició de qüestions clau, revisió de polítiques i delimitació del públic de la traducció i la interpretació jurídiques en els serveis públics. Revista de Llengua i Dret, 71, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2436/rld.i71.2019.3311

Welch, D., & Warde, A. (2015). Theories of practice and sustainable consumption. In L. A. Reisch & J. Thogersen (Eds.), Handbook of research on sustainable consumption (pp. 84–100). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783471270.00013

Welch, D., & Yates, L. (2018). The practices of collective action: Practice theory, sustainability transitions and social change. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 48(3), 288–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12168

Welch, D., & Yates, L. (2022). Approaching political action through practice theory. In R. Ballard & C. Barnett (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of social change (pp. 361–372). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351261562-34

Yanow, D., & Schwartz-Shea, P. (2014). Interpretation and method: Empirical research methods and the interpretive turn. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315703275