Activist translation of queer graphic novels: The case of Heartstopper in Turkey

Cihan Alan

Hacettepe University

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5220-3473

Abstract

In the context of a significant deterioration of LGBTQI+ rights in Turkey, the translation of the queer graphic novel, Heartstopper, into Turkish (as Kalp Çarpıntısı) was labelled “harmful for children” by the Board of Protecting Minors from Obscene Publication, a state mechanism that controls publications for children. The precarity of queer translation in the Turkish publishing industry raises the question of the potential for activist translation to disrupt anti-LGBTQI+ hegemonic discourses and their silencing of LGBTQI+ youth sexuality and identity in repressive contexts. The study on which this article is based investigated the performativity of Kalp Çarpıntısı as a translation and focused on the practices of translation agents who were involved in the translation, publication, and reception of Heartstopper in Turkey. It provides a qualitative analysis of Ömer Anlatan’s engagement with the graphic novel and its portrayal of LGBTQI+ youth, a semi-structured interview with the translator and an account of the reviews of the book. The study reveals the translator’s multimodal interventions in the text, driven by his professional background as a counsellor and his knowledge of the language used by the LGBTQI+ community in Turkey. It accounts for the unwavering support of the publisher despite public controversies and also for the timely sociopolitical impact of the translation in and beyond LGBTQI+ circles in Turkey. The compelling case of the Turkish translation of Heartstopper as a queer graphic novel reminds us that the solidarity of multiple agents is crucial in paving the way towards social and queer justice for children and youths generally in contexts of repression.

Keywords: graphic novel; queer translation; activism; performativity; social justice

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the rights of LGBTQI+ people in Turkey have increasingly deteriorated under the rule of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), a neoliberal, conservative, and authoritarian Islamist party (Coşar, 2015; Göregenli, 2015). This is attested to by the state’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, a measure aimed at preventing violence against women and domestic violence and redressing discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. In this context, the authorities’ labelling of publications on LGBTQI+ as muzır (harmful, obscene, or detrimental to health and children’s sexual development) has been on the rise. A case in point is the Turkish translation of Alice Oseman’s queer graphic novel, Heartstopper, which revolves around same-sex teenage romance.

What began in 2016 as a serialized webcomic and was then published as a graphic novel series by the Hachette Book Group in 2019, Heartstopper explores themes such as first love, friendship, coming out and mental health (Oseman, n.d., para. 3). It also deals with societal issues such as homophobia, peer victimization, eating disorders and the need for psychological support. Although its narrative style is predominantly non-didactic, Heartstopper raises awareness of the various situations faced by LGBTQI+ children and young adults (YAs) in their daily lives. Unlike many of its contemporaries, the graphic novel is notable for its inclusive representation of LGBTQI+ identities, featuring characters who identify as gay, bisexual, lesbian or transgender without relying on stereotypes. Heartstopper was translated into Turkish in 2021 by psychological counsellor and translator Ömer Anlatan and published by Yabancı Publishing under the title Kalp Çarpıntısı.

On 4 November 2021, the Board of Protecting Minors from Obscene Publications (BPMOP), which is in charge of executing the Law on the Protection of Minors from Obscene Publications under the Ministry of Family and Social Services, classified Kalp Çarpıntısı as harmful and obscene. In its report, the board claimed it could negatively affect the psychosocial, moral, and mental development of children under 18 (MFSS, 2021). It also relied heavily on moral and cultural arguments such as national values and family protection which were considered to be violated by the graphic novel’s inclusive portrayal of queerness. As a consequence, Kalp Çarpıntısı is sold in sealed envelopes and labelled as “harmful for children”.

In this sociopolitical climate, the publication of the Turkish translation of a graphic novel that portrays non-normative sexualities among children and YAs constitutes a perilous public exercise that disrupts the state-sanctioned condemnation and censorship of LGBTQI+ identities and contributes to creating deliberative spaces for advancing social justice for queer youths.

2. Performativity of queer activism in graphic novel translation

Translation enables the global circulation of queer graphic novels. At the same time, it affects the way they are received across cultural and national publishing industries. Aiming to investigate the translation of queerness in Kalp Çarpıntısı and its reception in Turkey, this study combined two key research areas in comics and graphic novels identified by Zanettin (2020): the translation strategies and the construction and negotiation of cultural and political identities in graphic novel translations (Zanettin, 2020, p. 77).

Translations may efface or reshape identities to different degrees, depending on the censorship mechanisms in the target publishing industry – for instance, selective publication, removal of sensitive content – particularly under authoritarian regimes (see Zanettin, 2018). At the same time, translation agents involved in the selection, translation, publication, and reception of the graphic novels may harness the potential of this genre to resist the dominant discourse and in so doing deliberately intervene to act as advocates of marginalized groups (Bandia, 2020). Baldo et al. (2021) emphasize the impact activist translations can have on society, noting that these translations can drive transformation and that activists use translation as part of their political agendas (p. 190). Activist translations aim to provoke readers into action, often involving interventionist strategies that renegotiate the meaning and tone of the original (Gould & Tahmasebian, 2020, p. 4).

Graphic novel translations that elucidate queer themes and introduce them through verbal and visual signs to target readers, particularly children and YAs, may have a disruptive effect on those discourses that consider child sexuality to be taboo. This taboo is not exclusive to Turkish society, as the original text is also disruptive in the Anglophone literature, which often reinforces gender stereotypes and heteronormativity (see Crisp, 2008; Epstein, 2013) and may remove queer elements through translations. The US ban on Heartstopper (Bearn, 2023) attests to the widespread societal resistance to queer-positive representation, particularly regarding children and YAs. This is why queer portrayals in children's literature are far from homogenous and why queerness can be problematized in various forms, even in Western contexts (Epstein & Chapman, 2021) that are often regarded as being more liberal (Epstein, 2017).

In this light, translating Heartstopper’s inclusive representation of queer identities, covering issues such as homophobia and mental health, entails a disruption of the dominant discourses with alternative ones. This was particularly the case when Heartstopper was translated into Turkish and the translation was published in the precarious Turkish publishing industry. Indeed, whereas Turkey’s publishing industry has mostly used the genre of graphic novel translations to promote modern Western values since the founding of the country in 1923 (Aksoy, 2016; Altıntaş, 2021), parents’ and educators’ conservatism (and the institutionalization of censorship) has since then limited the political potential of the children’s graphic novel genre, it having given way to a more globalized, humour- and entertainment-driven genre (Cantek, 2019). In this context, the only study available on the Turkish translation of Heartstopper to date (Abdal & Yaman, 2023), investigates the role of multiple mediators, including the hegemonic and resisting publics, in the dissemination of the translation. While it concludes that mediation is mostly a matter of conflict in autocratic social conditions, the present article focuses on acts of collaboration that are woven into these very conditions.

The focus on collaborative queer activism in graphic novel translation and reception requires a detailed examination of the cumulative practices of the translator, the publisher, and the readers and their discursive impact in context. Butler’s (1993) concept of performativity is particularly relevant in this regard. Defining performativity as “the reiterative and citational practice by which discourse produces the effects that it names” (p. 2), Butler reminds us that translation is not a mere intentional transfer of meanings across languages; nor is it a prediscursive phenomenon detached from its constitutive acts. As in the case of gender, translation is performative, involving stylized and iterative (Butler, 1993) speech acts (Austin, 1962/1975) that lead to meaningful transformations within normative systems (Bermann, 2014). Translation therefore constitutes a productive process for creating meanings in new contexts where translators prioritize specific aspects of a text based on sociopolitical contexts and their ideological stance (Tymoczko, 2010). Translators’ performative cultural transformations (Robinson, 2002) make an impression on their audience and the wider society. Through its performative nature, translation allows entrenched gender and sexuality regimes to be challenged, as Foucault (1978) discusses through the discursive productivity of power/knowledge.

Activism in translation is performed through the iteration of translation agents’ “dispositions” (Butler, 1990; see also Pym & Matsushita, 2018) to change normative societal structures. The transformative effects of performative translational acts are intertwined with specific institutional and social contexts, where they may generate new discourses, create alliances, and weave solidarity bonds in the target activist community (Baldo, 2020, p. 36). The performativity of queer activist translation mobilizes agents who seek to resist power/knowledge mechanisms to produce new discourses and foster solidarity around them (Baldo, 2020). The graphic novel genre, given its unique characteristics – such as facilitating communication through visual signs and targeting specific age groups – creates a compelling space for discourse production and shifts in meaning in receiving cultures. In the light of this, graphic novel translations provide a platform for activism against institutions that suppress queerness. Investigating this activist translation can illuminate queer phenomena that are often ignored or marginalized by dominant regimes of power/knowledge (Baer & Kaindl, 2018, p. 3) and reveal the role of collective activist efforts in reflecting social justice as a “communicational and social performance” (Boéri, 2023, p. 1).

3. Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative methodology in order to explore the ways in which queer activism is performed in the translation, the publication, and the reception of Heartstopper. Its data comprise the three volumes of Heartstopper (the source text, ST) and Kalp Çarpıntısı (the target text, TT), a semi-structured email interview with the translator, and reviews and comments from non-homophobic and activist voices. It combines a contrastive textual analysis of Heartstopper and Kalp Çarpıntısı using the paratextual data retrieved from the interview and the reviews.

The textual analysis first scrutinizes the Turkish translation of the three volumes to identify linguistic elements (i.e., nominal and verbal) related to non-binary romantic relationships, sexuality and desire, and also LGBTQI+ terminology and jargon in the context of visual and typographical signs. It then selects specific examples of queer subjectivity and non-binary relationships for in-depth contrastive analysis. To account for the interplay between linguistic, typographic, and pictorial signs in the comparative analysis of verbal elements, this study drew on Klaus Kaindl’s (1999, 2010) analytical framework for the translation of comics – more specifically, his translation strategies:

i. repetitio, retention of the source element as identical;

ii. adiectio, addition of linguistic or pictorial material that is not there in the original;

iii. detractio, reduction of source linguistic, pictorial, or typographic elements;

iv. transmutatio, change in the order of source linguistic or pictorial elements;

v. substitutio, replacement of the original linguistic, typographic, or pictorial material with relatively equivalent material; and

vi. deletio, removal of text or pictures in the translation.

To capture the performativity of a queer activist discursive change in the representation of LGBTQI+ children and YAs in the target culture, the findings arising from the textual analysis are then cross-examined against the translator’s motivations, his relationship with the publishing company, his lexical choices during the translation process, and with non-homophobic and activist voices – the author, critics, LGBTQI+ organizations, publishers, journalists, and bloggers. The analysis underscores the translational (para)textuality of the graphic novel in its specific socio-political context, emphasizing its performativity as a queer activist form of resistance and subversion in Turkey.

4. Contrastive analysis of Heartstopper and Kalp Çarpıntısı

Table 1 presents the linguistic elements which relate to LGBTQI+ that were identified in Kalp Çarpıntısı. They are categorized as nominal or adjectival or verbal, the number of occurrences in the text is indicated for each category and subcategory, with a calculation of the percentage to account for the proportion of the (sub)categories in relation to one another, and the corresponding linguistic units in Turkish and the original words or phrases.

Table 1. Linguistic categories in Kalp Çarpıntısı with LGBTQI+ references

|

Categories |

Number of occurrences |

Percentage |

TT/ST linguistic units |

|

|

NOMINAL/ADJECTIVAL |

Sexual identity label |

77

|

21.8 |

gey [gay], eşcinsel [homosexual, gay], lezbiyen [lesbian], biseksüel [bisexual], trans [trans], kuir [queer] |

|

Nouns or adjectives referring to gender and sexuality issues |

18 |

5 |

cinsel yönelim [sexuality], homofobik [homophobic], gey krizi [gay crisis] |

|

|

Nouns referring to romantic partner |

17 |

4.8 |

erkek arkadaş [boyfriend]; kız arkadaş [girlfriend] |

|

|

Nouns connoting homosexuality |

5 |

1.4 |

oğlan [lad], ragbi oğlanı [ragby lad] |

|

|

Derogatory terms |

3 |

0.9 |

ibne [fag/faggot], ibnetor [gaylord] |

|

|

Subtotal |

120 |

33.9% |

|

|

|

VERBAL |

Verbs involving romantic or sexual action |

69 |

20 |

öpmek, öp(üş)mek (reciprocal) [to kiss], boynunu morartmak/kızartmak [to bruise the neck], sarılmak [to hug], dizine oturtmak/dizine doğru çekmek [to sit on the lap/to pull onto the lap] |

|

Verbs on dating or being a couple |

48 |

13.6 |

takılmak/zaman geçirmek [to hang out], biriyle takılmak [to make out with someone], çıkmak/birlikte olmak [to go out/to be together/to date] flört etmek/flörtleşmek [to flirt], çift olmak [to be a couple] |

|

|

Verbs on coming out |

47 |

13 |

açılmak [to come out] |

|

|

Verbs referring to romantic feeling |

46 |

13 |

hoşlanmak [to like], aşık olmak/sevmek/sevgili olmak [to fall in love/to love/to be lovers], tutulmak [to fall in love with sb./to have a crush on sb.], abayı yakmak (idiom) [to fall in love] |

|

|

Verbs referring to sexual orientation |

11 |

3.1 |

hetero olmak/hetero bir çocuğa tutulmak [to be straight/to have crush on a heterosexual guy] |

|

|

Verbs referring to sexual intercourse |

7 |

2.0 |

yapmak [to do it, to make love], öpüşmeden fazlasını yapmak [to do anything more than kissing], kucağına atlamak [to jump on someone’s lap], dondurma yalamak [to lick ice-cream] |

|

|

Verbs referring to sexual attraction |

5 |

1.4 |

seksi olmak [to be sexy/hot] |

|

|

Subtotal |

233 |

66.1% |

|

|

|

|

TOTAL |

353 |

100% |

|

Among the nominal and adjectival categories, sexual identity labels constitute the most frequently used linguistic units, accounting for 21.8% of the total. The TT provides a comprehensive set of LGBTQI+ identity labels, including gey, lezbiyen, biseksüel, trans and eşcinsel.

Contrasting these terms with the ST reveals that they are retained through repetitio, supplemented with Turkish transliterations. Notably, gey and eşcinsel (homosexual) – a superordinate term in Turkish that encompasses both gay and lesbian identities – are used interchangeably for “gay”, although the latter refers more broadly to sexual orientation. As suggested in Table 1, the translator avoids the use of naturalized homoseksüel, a term associated with pathology and medicalization, owing to its negative connotations in Turkish (Yardımcı & Güçlü, 2013, p. 21). He opts to use the source term “gay” throughout his translation instead. Anlatan’s choice to discard pejorative terms and to adopt local LGBTQI+ activist terminology reflects his commitment to Turkish activists, to members of the LGBTQI+ community, and to young readers, to challenge the state’s attempts to “protect” them from non-normative gender identities and desires.

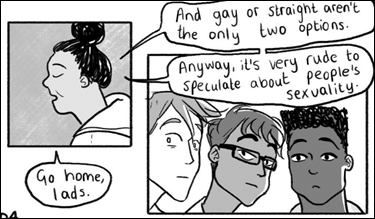

Although it is a less discriminatory and pejorative term, eşcinsel also expresses the markedness of sexual identity labels in homophobic discourses. This choice aligns with the translator’s strategy of providing clarity regarding LGBTQI+ identities. Heartstopper introduces children and YAs to various forms of homophobia and confronts them through verbal and visual cues. In Figure 1, for instance Nick challenges his brother, David, who scornfully remarks, “I just wanted to meet the guy who turned my little brother gay. … Should have always known you’d turn out to be gay!” (Oseman, 2020, p. 644). After Nick corrects him, stating, “I’m bi, actually,” David dismisses bisexuality, responding, “If you’re gonna be gay, at least admit you’re gay.” The translation replaces “gay” with eşcinsel, therefore highlighting David’s homophobic attitude and making his neglect of the distinction between sexual identities more explicit in Turkish.

Figure 1: Substitutio of “gay” with “eşcinsel” while retaining the original figure

Note. ST from Heartstopper (Oseman, 2020, p. 644); TT from Kalp Çarpıntısı (Oseman, 2020, 2021c, p. 644) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.)

The translator deliberately avoids the transliterated gey, opting instead for the generalized eşcinsel to highlight sexual identities in context. By emphasizing Nick’s correction of his bisexual identity, the translation reflects the heteronormative mindset in which non-normative gender labels are often generalized. In Turkish, eşcinsel may occasionally be used in heteronormative contexts as an umbrella term for non-binary identities, downplaying the nuances of sexual identities. This practice was particularly prevalent in the Turkish media before LGBTQI+ terminology became widespread (Gürsoy Ataman & Ataman, 2018, pp. 93–98). Anlatan’s use of eşcinsel, along with the repetitio of pictorial signs, values non-normative identity labels, countering the reductionist tendencies of such terms. His lexical choices reflect activist performativity, familiarizing readers with specific identity distinctions and the homophobic implications of other terms.

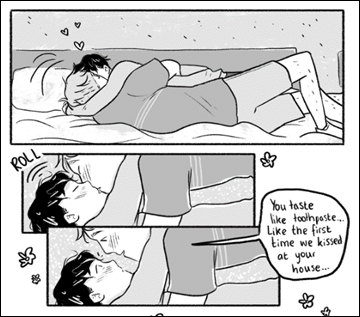

Another notable terminological choice is cinsel yönelim (sexual orientation), which replaces cinsellik (sexuality) in the ST. For example, Miss Singh, the physical education teacher, warns a group of boys speculating about Nick and Charlie’s relationship: “Ayrıca insanların cinsel yönelimleri hakkında konuşmak da çok kabadır” (Oseman, 2020, 2021a, p. 204) [Also, it’s very rude to talk about people’s sexual orientation]1.

Figure 2: Replacement of “sexuality” with “cinsel yönelim” [sexual orientation], while retaining the original figure

Note. ST from Heartstopper (Oseman, 2019a, p. 204); TT from Kalp Çarpıntısı (Oseman, 2019a, 2021a, p. 204) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.)

The shift from cinsellik to cinsel yönelim through adiectio reflects the translator’s ethical responsibility to use accepted language. This choice not only clarifies meaning but also serves a social function. In Kaos GL’s2 dictionary (Kaos GL, n.d.), cinsel yönelim is defined as an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction, contrasting with the often-misused term cinsel tercih (sexual preference), which implies choice (Gedizlioğlu, 2020, p. 49). Anlatan’s use of cinsel yönelim aligns with the terminology preferred by local LGBTQI+ activists, ensuring linguistic precision in the target context. The repetitio of pictorial signs, such as the boys attentively listening to Miss Singh, reinforces the pragmatic effect, further supporting the queerness of the graphic novel in the translation.

The term also underscores a significant legal sensitivity for LGBTQI+ activists in Turkey. While Article 10 of the Turkish Constitution guarantees equality before the law for all individuals, it does not explicitly include the term “sexual orientation”. LGBTQI+ activists in Turkey have long advocated the term’s inclusion in the Constitution as a reflection of the state’s responsibility to ensure social justice for all, including LGBTQI+ individuals (Köylü, 2016). Including the term in the translation helps to raise awareness among young readers about their social rights.

Although infrequent (0.9%), the category of derogatory terms includes an interesting strategy of substitutio. The use of ibne and ibnetor (a derivative of ibne with a French suffix) highlights LGBTQI+ children’s exposure to homophobia. In modern Turkish, ibne is a vulgar term derived from the Arabic ibn (meaning “son” or “boy”) and it refers offensively to a “passive homosexual male” (Türk Dil Kurumu, n.d.a). See, for instance, the following panel, which through substitutio maintains the homophobic insult’s impact.

Figure 3: Substitutio of the derogatory term “fag” with “ibne”

Note. ST from Heartstopper (Oseman, 2019b, p. 495); TT from Kalp Çarpıntısı (Oseman, 2021b, p. 495) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.)

This translation draws attention to common issues such as homophobia, bullying and hate speech that LGBTQI+ children face. The transfer of these derogatory meanings through substitutio serves a social function in the target culture, enhancing the visibility of LGBTQI+ children and raising their awareness of homophobic insults. During the past decade, ibne has gained a liberating meaning through the slogan “Velev ki3 ibneyiz!” [What if we are fags!], a response to AKP’s homophobic policies. The translator’s decision to retain this offensive language, without euphemizing it – as seen in the Netflix adaptation (Walters, 2022–2024), where “fag” is softened to eşcinsel) – reflects an activist stance. This choice, along with the preservation of pictorial and typographic signs, reinforces the social message of the graphic novel against homophobia.

Another instance of substitutio occurs with the term oğlan (“boy” or “son”). When Nick playfully refers to Charlie as “lads”, the translation uses oğlan (Figure 4): “Neden bir şeyler yiyip içmeye çıkmıyoruz o zaman, kanka? Hadi, OĞLAN, OĞLAN, OĞLAN” (Oseman, 2020, 2021a, p. 172) [Why don’t we go out for eating and drinking then, mate? Come on, BOY, BOY, BOY].

Figure 4: Substitutio of the word “fag” with “oğlan”

Note. ST from Heartstopper (Oseman, 2019a, p. 172); TT from Kalp Çarpıntısı (Oseman, 2019a, 2021a, p. 172) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.)

In Ottoman society, oğlan historically referred to a young male engaged in sexual service; it was associated with pederasty across all social classes (Oksaçan, 2012). This practice, rooted in Eastern Roman and Middle Eastern traditions (Oksaçan, 2015, p. 1), represents a specific form of homosexuality shaped by historical contexts (İnceoğlu & Çoban, 2018, p. 22). Recently, the Turkish Language Association revised the derogatory definition of oğlan, which described it as a “young male pervert who sexually serves other men”, into the milder “a person sexually serving other men for pleasure” (Türk Dil Kurumu, n.d.b). Whether or not the tone of these definitions differs and the Turkish Language Association condemns its connotation, Anlatan carried the historical meaning of the word into his translation. In the panel above, the replaced linguistic element and the repeated typographic and pictorial signs work together to reinforce queer meaning in the translation. Although other Turkish words such as çocuk (boy), veled (son), or kanka (mate) could have conveyed a similar pragmatic effect, the translator chose the less preferable oğlan to introduce a queer meaning, or “acqueer” (Epstein, 2017). This usage revives a domestic perception of homosexuality and radically transforms the context. This choice reflects resistance to dominant societal views on homosexuality, freeing oğlan from its derogatory connotations, much like the term ibne. By retaining the original typographic emphasis (i.e., capitalized letters for marked intonation), the word oğlan is spotlighted with its archaic meaning. In addition, the pictorial signs enhance the queer reading, as the protagonists are depicted in an intimate physical interaction, suggesting a romantic relationship rather than mere friendship.

Verbs account for 66.1% of the linguistic elements related to non-binary romantic relationships, sexuality and desire in Heartstopper, playing as they do a crucial role in inclusive LGBTQI+ representation. These verbal elements are further enhanced by typographic and pictorial signs throughout the graphic novel. The BPMOP report (MFSS, 2021) in particular condemned these visual and linguistic elements that referred to the actions in same-sex relationships – hugging, kissing and expressing affection – which they considered “harmful” and “obscene” and contrary to both Turkish traditional moral values and societal norms established by the Turkish Penal Code (2005) and the Basic Law of National Education.

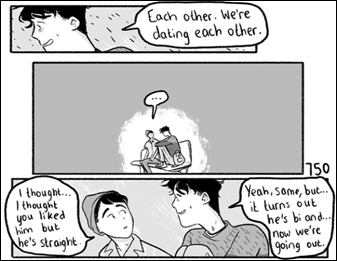

Notably, the most prominent verbs refer to romantic or sexual actions (20%), being in a relationship (13.6%), coming out (13%) and expressing romantic feelings (13%). Kissing is a frequently depicted action, accompanied by both typographic and visual signs. In Figure 5, Nick and Charlie kiss and hug in bed, with Nick commenting, “Diş macunu kokuyorsun … Senin evinde ilk kez öpüştüğümüzdeki gibi …” [You smell like toothpaste, like the first time we kissed at your house] (Oseman, 2020, 2021c, p. 728).

Figure 5: Verb referring to romantic or sexual action: “kissing”

Note. ST from Heartstopper (Oseman, 2020, p. 728); TT from Kalp Çarpıntısı (Oseman, 2020, 2021c, p. 728) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.)

Verbs in speech bubbles are consistently retained through substitutio. The graphic format of Heartstopper features black-and-white ink illustrations, hard-frame panels, large speech bubbles and varying font sizes, creating a fast-paced narrative that highlights the characters’ emotions. Graphic elements such as hearts and flowers enhance this emotional depth, while action epithets such as “ROLL”, translated as YUVARLAN [roll], convey direction and intensity, with the capital letters and large font size adding emphasis.

One of the key themes in Heartstopper is the portrayal of coming out as LGBTQI+ in children. The plot centres on the protagonists’ coming-out journeys, both individually and as a couple. The phrasal verb "to come out" is repeatedly used in the ST (n = 47) and is consistently translated as açılmak (to come out, lit. “to be open up”) through substitutio, without any omissions.

Figure 6: Nick comes out to his mother

Note. ST from Heartstopper (Oseman, 2019b, p. 551); TT from Kalp Çarpıntısı (Oseman, 2019b, 2021b, p. 551) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.) BT [Mother: Thank you for telling me. Nick: sob (onomatopoeic)]

While the narrative addresses the challenges of coming out to friends and family, the characters are not depicted as traumatized victims. The accompanying pictorial signs contribute additionally to a positive tone. For instance, in Figure 6, Nick comes out to his mother as bisexual and she responds warmly. Similarly, in Figure 7, Charlie reveals his relationship with Nick to Tao, who reacts positively, despite Charlie initially keeping the relationship secret to protect Nick, who was not ready to come out. In both scenes, positive responses are reinforced by pictorial signs, preserved through repetitio.

Figure 7: Charlie reveals his relationship with Nick to Tao Xu

Note. ST from Heartstopper (Oseman, 2020, p. 750); TT from Kalp Çarpıntısı (Oseman, 2020, 2021c, p. 750) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.) BT [Charlie: Each other. We are dating each other. Tao: I … I thought you liked him, but he is heterosexual. Charlie: Yes, exactly, but it turns out he’s bi and now we’re dating.]

Throughout the graphic novel, many verbs and idioms in the speech bubbles provide insights into the actions and states that the non-binary characters engage in. Verbs related to dating/being a couple (13.6%) – for example, takılmak/zaman geçirmek [to hang out], biriyle takılmak [to make out with someone] – and romantic feelings (13%) – for example, hoşlanmak [to like], abayı yakmak [to fall in love] – are rendered through substitutio. The same procedure applies to references to sexual intercourse (2%), with euphemistic phrases such as yapmak [to do it], öpüşmeden fazlasını yapmak [to do anything more than kissing] and dondurmasını yalamak [to have a lick of someone’s ice cream] preserved in the TT. The word “sexy” appears only once through repetitio, while seksi (a transliterated loanword) is replaced in expressions such as “to be hot” (n = 4).

These examples demonstrate how substitutio and adiectio contribute to an interventionist translation that highlights the queerness of the ST for the target audience. Other substitutio operations in linguistic elements and repetitio in typographic and pictorial elements help to maintain the original representation of LGBTQI+ sexuality and desire in children and YAs in Turkish. More radical operations such as detractio, transmutatio, and deletio are absent from the translation. The translator’s use of both interventionist and retention strategies ensures that transformative meanings are conveyed in the receiving culture.

The foregrounding of queerness using the language of queer activists, leveraging domestic queer terms, and making source concepts explicit, together with the retaining all the pictorial and typographic signs, perform iterative multimodal translation acts that challenge entrenched gender and sexuality regimes (Foucault, 1978).

5. Production and publication of Kalp Çarpıntısı: Ömer Anlatan’s interview

To grasp fully the activist and performative nature of the Turkish translation of Heartstopper, it is essential to consider the agents involved in its production and its relation to verbal and non-verbal textual elements (Kaindl, 1999, p. 285). Epsilon Publishing House, a giant publisher of fiction and non-fiction books in Turkey, announced its decision to publish the Turkish translation of Heartstopper in March 2020 through its social media accounts (Epsilon Yayınevi, 2020). Soon after the announcement, many pro-government news portals and troll social media accounts began speculating about the news, launching a hate campaign against LGBTQI+ people. The process ended up with Epsilon’s relinquishment of its rights to publish the translation. Despite all these unfavourable conditions, though, Yabancı Publishing House (“Yabancı”), affiliated to the Ithaki Publishing Group, acquired the publication rights to Heartstopper. Ömer Anlatan, a professional psychological counsellor, volunteered for the translation, driven by both professional responsibility and personal interest in the series (personal communication, October 23, 2023). Individuals are socialized into their professions through mechanisms such as formal education, specialized training, practical experience, and peer interactions. This process equips them with specific knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavioural patterns relevant to their field. As a translator, Ömer Anlatan’s inclusive attitude towards LGBTQI+ individuals, along with his ethical stance and professional responsibilities, informed his decision to translate Heartstopper.

According to Baker (2010), activist translation is inherently political, starting from the selection of the material. Anlatan’s decision to translate Heartstopper was a political act that aligns with his ethical stance against violence and discrimination, which resonates with his translation choices. He emphasizes that his translation strategies constitute a form of activism, aiming to avoid the reproduction of harmful language while advocating marginalized groups (O. Anlatan, personal communication, October 23, 2023). His deliberate use of LGBTQI+ terminology, approved by local activists, highlights the cis-heteronormative discourse of homophobic characters and establishes a clear distinction between the voices of the LGBTQI+ characters and their homophobic peers. Furthermore, given the positive and inclusiverepresentation of LGBTQI+ issues in Heartstopper, Anlatan’s translation serves to inform young readers about what is “good” and “bad” regarding these issues, shedding light on the gender-related social realities of their culture. He explains his decision to include homophobic terms such as ibne and ibnetör [fag] as a reflection of contextual meaning, intending to convey that such language is wrong, offensive and insulting (Ö. Anlatan, personal communication, October 23, 2023). Therefore, the translator’s refusal to perpetuate discriminatory discourses and his emphasis on avoiding homophobia constitutes a performative translation that challenges the dominant repressive narratives surrounding gender and sexuality in Turkish society.

For Foucault (1979, p. 36), power/knowledge is not solely about repression; it also creates satisfaction, shapes knowledge, and produces discourses. Mechanisms of power – governance, legislation, media production, religious preaching, healthcare, and policymaking – contribute to the entrenchment of a binary gender regime across all spheres of society. In this discursive context there is a prevailing silence regarding LGBTQI+ children in Turkish cultural institutions. An activist translator, however, serves as a voice-giver who “puts into words the perspectives and experiences of oppressed and silenced peoples” (Gould & Tahmasebian, 2020, p. 2). By conveying the verbal and non-verbal signs related to LGBTQI+ issues that are unique to children and YAs, Anlatan positions himself as a voice for those who remain passive subjects of the power/knowledge mechanisms.

Anlatan identifies his admiration for the graphic novel and his desire to convey its important messages for queer youth in Turkish as his primary motivation for translating it. He notes that the graphic novel genre is more effective than prose for reaching a wider audience (Ö. Anlatan, personal communication, October 23, 2023). In Turkey, non-normative sexualities in childhood are often dismissed by institutions such as family and education. Anlatan’s efforts to convey messages about identities and sexualities are performative, contributing to new discourses regarding LGBTQI+ children. However, this effort faces resistance, as attested to by the BPMOP report. This is the report which accused Heartstopper of promoting a homosexual lifestyle that is incompatible with Turkish and Islamic values, reflecting the AKP’s post-2021 stance that equates morality to Islamic values while denying LGBTQI+ existence. Despite these challenges, Anlatan employs strategies that enhance the queerness of source meanings, retain non-verbal elements and explicate terms, and therefore transform the discourse. The narrative structure of the graphic novel effectively appeals to YAs, challenging dominant heteronormative narratives through portrayals of queer children in romantic contexts and in their coming-out experiences. Since the progression of performative actions is influenced by social and institutional conditions (Baldo, 2021, p. 36), the format of the material also accelerated state responses to the translation.

Being a translator-activist necessitates an understanding of the social and political context for those whose voices are amplified (Gould & Tahmasebian, 2020, p. 2). An activist translator employs language – whether dialect, slang, or accepted terminology – in ways that can effect change within specific communities. Supporting this perspective, Anlatan emphasizes the importance of language transformation, adopting the motto that “change begins in language”. He explains that he used the translation dictionary published by Kaos GL to align his word choices with the preferences of LGBTQI+ communities while avoiding the discourse of violence and discrimination – for example, opting for bilim insanı (lit. science person) over bilim adamı (lit. science man) and rendering gendered pronouns in English with gender-neutral terms such as kişi (person), birey (individual), and insan (human) (Ö. Anlatan, personal communication, October 23, 2023).

Gedizlioğlu (2020, p. 8), the editor of LGBTİ+ Hakları Alanında Çeviri Sözlüğü [Translation Dictionary in the Field of LGBTQI+ Rights], states that the dictionary compiles concepts related to sexual identity, sexual orientation, and gender or sexuality regimes as understood by the subjects themselves. By using this dictionary as a reference, the translator fosters a non-discriminatory and non-heteronormative discourse, in this way preventing the reproduction of local anti-LGBTQI+ narratives and highlighting LGBTQI+ individuals as “political subjects who produce discourses from their own existence” (p. 8). For instance, his emphasis on the distinct nature of bisexuality, particularly in differentiating between gey [gay] and eşcinsel [homosexual] in Turkish, exemplifies translation performativity. This sensitivity aligns Anlatan’s practice with that of LGBTQI+ activists. His attention to LGBTQI+ activist terminology reflects his commitment to non-discriminatory and accepted language use. Therefore, adopting LGBTQI+ terminology is not merely a choice but an expression of the translator’s ongoing efforts at resisting the discriminatory discourses of the heteronormative regime. As a “mobilised translator” (Tymoczko, 2010), Anlatan creates a space for resistance, initiating discourse on the inclusivesubjectivity of LGBTQI+ children and challenging the silence surrounding non-normative child sexuality.

The translator’s political productivity is echoed by the editors of Yabancı. Anlatan emphasizes that the publishing house did not interfere with his translational choices (Ö. Anlatan, personal communication, October 23, 2023), indicating a collaborative effort to enact changes in domestic discourses surrounding LGBTQI+ children. Founded in 2013, Yabancı primarily publishes fiction and non-fiction related to women’s and YA’s issues. In an interview, chief editor Ece Çavuşlu (2021) noted that Yabancı has a history of publishing LGBTQI+ literature based on its “inclusive publication policy”. Yabancı’s translation was labelled a “brainwash operation” on social media during the summer of 2021, prompting conservative groups to urge families to protest its release (Çavuşlu, 2021), which ultimately led to its designation as an “obscene publication”. The editors of Yabancı, as agents in Turkey’s publishing industry, therefore fulfil a distinctive activist role. The publishing house remained committed to translating the graphic novel despite the social backlash, and to publish it shortly after Turkey withdrew from the Istanbul Convention in March 2021. It also continued to disseminate Heartstopper despite a 40% tax imposed on books labelled as “harmful” in Turkey and the subsequent impact on sales. In the light of this, their niche publication policy focused on youths, women, and LGBTQI+ topics grants them symbolic rather than economic gain. It is in the specific circumstances of the translation that activism takes shape and can be appraised (Gould & Tahmasebian, 2020, p. 4). Therefore, the Turkish translation of Heartstopper and its publication in Turkey constitute not just a routine publication effort but a performative process involving multiple actors aiming to create social change at a critical moment.

In conclusion, Anlatan’s interview highlights the collaborative activist nature of Heartstopper’s Turkish translation. Anlatan’s activist translation strategies, combined with Yabancı’s commitment to publishing LGBTQI+ content, converged to challenge the entrenched discourses of heteronormativity in Turkey. Their combined efforts resulted in a performative translation process aimed at generating social change and amplifying LGBTQI+ voices in a culture where they are often silenced.

6. Reception of Kalp Çarpıntısı: reviews and comments in activist circles

The activist nature of the translation of Heartstopper into Turkish is intricately linked to the concept of “solidarity” in a sociopolitical landscape that often marginalizes queer voices. Anlatan’s performative translation not only engages a wide array of stakeholders – including authors, literary critics, streaming platforms, queer activists, and publishers – but also mobilizes them to challenge repressive state mechanisms collaboratively. This collective effort aims to forge new discourses around LGBTQI+ identities, particularly in a climate where societal norms frequently dismiss or actively suppress queer representation.

Following the classification of Heartstopper as “harmful to minors” by the BPMOP in September 2021, Alice Oseman swiftly expressed her support for Yabancı on social media. This public endorsement not only showcased solidarity with the publishing house but also highlighted the plight of LGBTQI+ individuals in Turkey. Oseman extended her support further by announcing via her Twitter (now X) account that she was making donations to two prominent LGBTQI+ organizations in Turkey – Lambdaistanbul and the Social Policy, Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Studies Association (SPoD). Such gestures underscore the critical role of transnational support networks, which include organizations such as the EU, the Consulate-General of Sweden and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung in reinforcing the necessity for solidarity among LGBTQI+ communities facing systemic oppression. The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association Europe (ILGA) also highlighted the censorship of the graphic novel in its annual report, categorizing it as a violation of freedom of speech. This external validation enhances solidarity and illustrates how the translation process has catalyzed broader engagement among various activist groups, in this way emphasizing the interconnectedness of local and global struggles for LGBTQI+ rights.

The enthusiasm and commitment exhibited by both the translator and the publisher starkly contrast with the reluctance of established firms such as Epsilon to engage with LGBTQI+ narratives. This solidarity network, built on a “shared precarity” (Baldo, 2020, p. 32), united activists in their defence of LGBTQI+ children’s rights and catalyzed activist solidarity resistance. As Tymoczko (2010, p. 230) notes, activist translators often collaborate with others in common endeavours. In this case, Anlatan’s performative translation, as described by Baldo (2020, p. 39), involved engaging with fellow activists to initiate political and ideological actions grounded in shared principles. Anlatan’s strategies for producing discourses on LGBTQI+ children, informed by his professional background and ethical stance, motivated Yabancı to publish the graphic novel as a form of resistance against the dominant sexual regimes in Turkey. This solidarity extends beyond the translator–publisher relationship: following the censorship of the translation, LGBTQI+ activists and their allies recognized Yabancı’s efforts by awarding them the 2021 Freedom of Thought and Expression Award from the Turkish Publishers Association for their work on Heartstopper, La Vie D'Adele, and Reasonable Doubt. Ece Çavuşlu emphasized in her acceptance speech that they felt supported and would continue their egalitarian and inclusive publication policy (“Düşünce ve ifade özgürlüğü ödülleri sahiplerini buldu ”, 2022, para. 6). Precarious conditions faced by translation efforts in Turkey’s dominant gender regimes and political context also function as a springboard for solidarity.

Indeed, public interest in Heartstopper grew only after the censorship, particularly that around the series adaptation on Netflix. Netflix Türkiye chose not to cancel the project, even though the show was aired with the label “+18” and a note indicating it was based on a book "harmful for minors", according to the Turkish Ministry of Family and Social Services. Although criticized for altering the series’ maturity rating from 13+ to 18+ (Aydın, 2022), Netflix continued to air Heartstopper, further increasing the visibility of the graphic novel’s translation.

Reviews from various platforms between 2021 and 2023 highlight the solidarity with the translation and with its representation of LGBTQI+ children in Turkey. For example, Bawer (2022) from the queer online platform Velvele underlined the translation’s role in giving voice to the lived experiences of LGBTQI+ youth, urging adult LGBTQI+ individuals to acknowledge past injustices and embrace the authentic identities of younger generations. Similarly, Arman (2022) from the Kazan Kültür blog page praised the graphic novel for providing an expansive space for empathy and for depicting the complexities of LGBTQI+ lives, and conveying that sexuality is but one facet of their identities. Furthermore, Şahin (2022) from Aposto, an online newspaper, highlighted the way in which Heartstopper challenges conventional stereotypes associated with “rainbow capitalism” by portraying queer youths who navigate the trials of adolescence and homophobia through the power of friendship and solidarity. These varied perspectives not only affirm the translation’s capacity to foster solidarity among activists, but also enhance the understanding of LGBTQI+ experiences in Turkey. In addition, some reviews focused on the enactment of precarity as a site for solidarity. Bawer (2022) notably connected the censorship of Heartstopper with historical instances of repression, such as the seizure of Kaos GL Magazine’s 2006 issue, which the authorities considered to be “pornographic”. This historical parallel illustrates the ongoing struggle for representation and freedom of expression in Turkey and highlights how censorship often incites greater discourse about marginalized narratives. These reviews indicate that the translation of Heartstopper has fostered a solidarity that extends beyond mere collective resistance to censorship; rather, it reflects a discursive production regarding LGBTQI+ children and the precarity of publishing on this issue in Turkey – which ultimately involves the activists as part of the translation’s performativity.

Tymoczko (2014) argues that the solidarity arising from translations should not be limited to reactive resistance; instead, she advocates a proactive form of activism where translators engage in diverse initiatives (p. 212). In this context, the translation of Heartstopper exemplifies such proactive solidarity, particularly through its focus on children. For instance, the Association of Families and Friends of LGBTQI+ in Turkey (LISTAG), founded in 2008, has intensified its advocacy following the censorship of the translation amid increasing anti-LGBTQI+ government actions. LISTAG has organized numerous meetings and webinars raising issues affecting LGBTQI+ children, urging politicians, including opposition MPs, to listen to the voices of parents striving to protect their children (e.g., “LİSTAG: Yürüyen yürüsün”, 2022; LISTAG, 2023; Tur, 2023). This illustrates the ways in which translations can transform activist engagement and shift the focus towards specific themes (Baldo, 2020, p. 36) by increasing the sustained participation of such activist groups in decision-making processes on social policies for children.

Finally, the translation has inspired various forms of activism, as evidenced by a book club hosted at Kıraathane in Istanbul, moderated by Karin Karakaşlı, an author of children’s books and a translator. The club engaged participants in discussions about the implications of labelling books as “harmful”, fostering community dialogue that reinforces the significance of the translation. Activists have collectively adopted the slogan “LGBTİ+ çocuklar vardır!” [LGBTQI+ children do exist!] in their advocacy efforts, reflecting a growing awareness and affirmation of LGBTQI+ children’s rights (Bawer, 2022, para. 25). Furthermore, Yabancı was motivated to translate subsequent volumes of Heartstopper (Çavuşlu, 2021), while Anlatan was inspired to translate another queer novel, Only Mostly Devastated, by Sophie Gonzales. These developments indicate that the performative translation of Heartstopper has not only generated solidarity among activists focused on the notion of “children”, but has also fostered a proactive stance, highlighting the potential of translation as a tool for social change and advocacy.

7. Conclusion

Kalp Çarpıntısı, the Turkish translation of Alice Oseman’s graphic novel, Heartstopper, disrupts the dominant discourse surrounding LGBTQI+ children and YAs in the country’s repressive social conditions. Through an analysis of translational strategies regarding both verbal and non-verbal textual elements, the study highlights the iterative, multimodal acts of translation, adopting an inclusive and supportive stance towards LGBTQI+ children and YAs in the context of reception. Anlatan draws on his professional background, ethical stance, and ideological beliefs and focuses on the unique representation of queerness in Heartstopper. Through retention, substitution, and addition strategies in Kalp Çarpıntısı he weaves this representation into the sociopolitical context of reception in Turkey, a context marked by both government repression and solidarity in anti-homophobic, queer activist circles. Alongside the translator’s performativity, Yabancı Publishing’s radical and niche publication practices serve as a driving force for the formation of solidarity among various circles, including publishers, authors, activists, non-governmental organizations, and the media.

The performativity of queer activism rests on a collective endeavour, sustained by the translator, the publisher, and the wider public, to introduce discourses on queerness and same-sex sexuality in Turkey. It extends beyond the mere importation of a graphic novel to create a space for dealing with social justice and for including LGBTQI+ children and YAs. Translation serves as a site of resistance and solidarity where the representation of LGBTQI+ children is contested, and where precarity (censorship of or aggression towards homophobic and transphobic groups) becomes a springboard for solidarity. While the hegemonic discourse in Turkey labels LGBTQI+ individuals and communities as deviant and immoral, often rendering LGBTQI+ children and YAs invisible in or targeted by legal, political, and educational contexts, the translation of Heartstopper and its publication in Turkey have given visibility to LGBTQI+ identities in Turkey. The translation, the publication, and the reception of the graphic novel have subverted mainstream publishing practices and prompted a clash of discourses in Turkey’s public sphere. This case reminds us that the sociopolitical impact of activist translations of queer texts in advancing social justice rests on the solidarity of multiple agents and on the timeliness of the translation in its context of reception.

Dedication

This article is dedicated to Berke Dönbak, a great fan of Heartstopper, who passed away in the Kahramanmaraş (Turkey) earthquakes on 6 February 2023.

References

Abdal, G., & Yaman, B. (2023). Mediatorship in the clash of hegemonic and counter publics: The curious case of Heartstopper in Turkey. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 18(2), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.23014.abd

Aksoy, N. B. (2016). Adventures of the graphic novel in Turkey. In K. Muschalik & F. Fiddrich (Eds.), Sequential art: Interdisciplinary approaches to the graphic novel (pp. 3–10). Inter-Disciplinary Press. https://doi.org/10.1163/9781848884472_002

Altıntaş, Ö. (2021). İlk Türk popüler edebiyat eserlerinde çeviri yoluyla milli kimlik inşası. Folklor Edebiyat Dergisi, 27(3), 839–855. http://doi.org/10.22559/folklor.1613

Arman, T. K. (2022, September 27). Heartstopper: Aşkı kucaklamak. Kazan Kültür. https://kazankultur.com/heartstopper-aski-kucaklamak/

Austin, J. L. (1962/1975). How to do things with words. Harvard University Press.

Aydın, E. (2023, November 25). Netflix dizisi Heartstopper iki devam sezonu için onay aldı. Kayıp Rıhtım. https://kayiprihtim.com/haberler/dizi/heartstopper-2-sezon-ve-3-sezon-onayi/

Baer, B. J., & Kaindl, K. (2018). Introduction: Queer(ing) translation. In B. J. Baer & K. Kaindl (Eds.), Queering translation, translating the queer: Theory, practice, activism (pp. 1–10). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315505978-1

Baker, M. (2010). Translation and activism. In M. Tymoczko (Ed.), Translation, resistance, activism (pp. 23–41). University of Massachusetts Press.

Baldo, M. (2020). Activist translation, alliances, and performativity: Translating Judith Butler’s Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly into Italian. In R. R. Gould & K. Tahmasebian (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and activism (pp. 30–48). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315149660-3

Baldo, M., Evans, J., & Guo, T. (2021). Introduction: LGBT/queer activism and translation. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 16(2), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.00051.int

Bandia, P. F. (2020). Afterword: Postcolonialism, activism, and translation. In R. R. Goul, & K. Tahmasebian (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and activism (pp. 515–520). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315149660-31

Bawer (2022, April 28). Heartstopper: LGBTİ+ çocuklara sevgi dolu bir mektup. Velvele. https://velvele.net/2022/04/28/heartstopper-lgbti-cocuklara-sevgi-dolu-bir-mektup/

Bearn, E. (2023, November 29). The graphic novel was banned in America – but Netflix rightly snapped it up. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/books/childrens-books/review-heartstopper-volume-5-alice-oseman/

Bermann, S. (2014). Performing translation. In S. Bermann & C. Porter (Eds.), A companion to translation studies (pp. 285–297). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118613504.ch21

Boéri, J. (2023). Steering ethics toward social justice: A model for meta-ethics of interpreting. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 18(1), 1–26, https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.20070.boe

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and subversion of identity. Routledge.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of “sex”. Routledge.

Cantek, L. (2019). Türkiye’de çizgi roman. İletişim.

Coşar, S. (2015). Suggestions for political sphere. In M. Köylü (Ed.), Situation of LGBTI rights in Turkey and recommendations (pp. 19–27). Kaos GL.

Crisp, T. (2008). The trouble with Rainbow Boys. Children’s literature in education, 39(4), 237–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-007-9057-1

Çavuşlu, E. (2021, November 6). “Muzır” kitaplar: Ece Çavuşlu ile ‘Kalp Çarpıntısı’ serisi üzerine [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzF8lAYauSA&t=500s&ab_channel=SusmaPlatformu

Düşünce ve ifade özgürlüğü ödülleri sahiplerini buldu. (2022, March 16). Bianet. https://bianet.org/haber/dusunce-ve-ifade-ozgurlugu-odulleri-sahiplerini-buldu-259148

Epsilon Yayınevi [@epsilonayinevi]. (2020, March 5). Yazarın en tatlısı. :) Heartstopper Epsilon’da [Post] X. https://x.com/epsilonyayinevi/status/1235576979119681537

Epstein, B. J., & Chapman, E. (2021). Introduction. In B. J. Epstein & E. Chapman (Eds.), LGBTQ+ literature for children and young adults (pp. 1–10). Anthem Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1zvccfh.6

Epstein, B. J. (2013). Are the kids alright?: Representations of LGBTQ characters in children’s and young adult literature. HammerOn Press.

Epstein, B. J. (2017). Eradicalization: Eradicating the queer in children’s literature. In B. J. Epstein & R. Gillett (Eds.), Queer in translation (pp. 118–128). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315603216-16

Erem, O. (2021, March 6). LGBT: İktidarın LGBTİ+ karşıtı söyleminin arkasında ne var?. BBC News Türkçe. https://www.bbc.com/turkce/haberler-turkiye-56292769

Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality: An introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1976).

Foucault, M. (1979). Truth and power: Interview with Alessandro Fontano and Pasquale Pasquino. In M. Morris & P. Patton (Eds.), Michel Foucault: Power, truth, strategy (pp. 29–48). Feral Publications.

Gedizlioğlu, D. (Ed.). (2020). LGBTİ+ hakları alanında çeviri sözlüğü. Kaos GL.

Gould, R. R., & Tahmasebian, K. (2020). Introduction: translation and activism in the time of the now. In R. R. Gould & K. Tahmasebian (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and activism (pp. 1–10). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315149660-1

Göregenli, M. (2015). Conservatism in terms of the control of sexual and gender identities. In M. Köylü (Ed.), Situation of LGBTI rights in Turkey and recommendations (pp. 11–18). Kaos GL.

Gürsoy Ataman, G., & Ataman, H. (2018). Halkımız ne der? Türkiye’de ilk onur yürüyüşü girişimi, yazılı basin, gazeteciler ve heteroseksizm. In Y. İnceoğlu & S. Çoban (Eds.), LGBTİ bireyler ve medya (pp. 81–109). Schola.

ILGA. (2021). Annual review of the human rights situation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and intersex people in Turkey covering the period of January to December 2021. https://www.ilga-europe.org/sites/default/files/2022/turkey.pdf

İnceoğlu, Y., & Çoban, S. (2018). Türkiye’de nefret, ötekileştirme, medya ve LGBTİ’ler. In Y. İnceoğlu & S. Çoban (Eds.), LGBTİ bireyler ve medya (pp. 13–45). Schola.

Kaindl, K. (1999). Thump, Whizz, Poom: A framework for the study of comics under translation. Target, 11(2), 263–288. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.11.2.05kai

Kaindl, K. (2010). Comics in translation. In Y. Gambier & L. Van Doorslaer (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation studies (Vol. 1) (pp. 36–40). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/hts.1.comi1

Kaos GL. (n.d.). Who are we? Kaos GL Derneği. https://kaosgldernegi.org/en/about-us/who-are-we

Köylü, M. (Ed.). (2016). Aile ve sosyal politikalar bakanlığı için LGBT hakları el kitabı. Kaos GL. https://kaosgldernegi.org/images/library/2016aspb-iin-lgbt-haklari-el-kitabi.pdf

LİSTAG: Yürüyen yürüsün ama bizim de ifade özgürlüğümüzün önünü açın. (2022, September 17). Serbestiyet. https://serbestiyet.com/haberler/listag-yuruyen-yurusun-ama-bizim-de-ifade-ozgurlugumuzun-onunu-acin-104041/

LİSTAG (2023, January 25). LİSTAG olarak Meclis’teki tüm milletvekillerine tekrar sesleniyoruz!. LİSTAG. https://listag.org/2023/01/25/listag-olarak-meclisteki-tum-milletvekillerine-tekrar-sesleniyoruz/

Ministry of Family and Social Services [MFSS]. (2021). Board decision Nb. 2021/04 on protecting minors from obscene publication. https://s3.fr-par.scw.cloud/fra-susma24-tr/2022/03/kalpcarpintisi_compressed.pdf

Oksaçan, H. E. (2012). Eşcinselliğin toplumsal tarihi. Tekin.

Oksaçan, H. E. (2015). Sultanlar devrinde oğlanlar. Agora Kitaplığı.

Oseman, A. (2019a). Heartstopper (Vol. 1). Hodder Children’s Books.

Oseman, A. (2019b). Heartstopper (Vol. 2). Hodder Children’s Books.

Oseman, A. (2020). Heartstopper (Vol. 3). Hodder Children’s Books.

Oseman, A. (2021a). Kalp Çarpıntısı (Vol. 1) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.). Yabancı Yayınları. (Original work published 2019).

Oseman, A. (2021b). Kalp Çarpıntısı (Vol. 2) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.). Yabancı Yayınları. (Original work published 2019).

Oseman, A. (2021c). Kalp Çarpıntısı (Vol. 3) (Ö. Anlatan, Trans.). Yabancı Yayınları. (Original work published 2020)

Oseman, A. (n.d.). The history. Alice Oseman. https://aliceoseman.com/heartstopper/the-history/

Robinson, D. (2002). Performative linguistics: Speaking and translating as doing things with words. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203222850

Penal Code of Turkey, Volume II Special Provisions, Art 226, §1–7 (2005). https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-REF(2016)011-e

Pym, A., & Matsushita, K. (2018). Risk mitigation in translator decisions. Across Languages and Cultures, 19(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2018.19.1.1

Şahin, İ. G. (2022, July 31). Kuir çocukların da yaşlanabileceği bir dünya: Heartstopper. Aposto. https://aposto.com/s/kalp-carpintisi

Tur, M. (2022, October 31). LGBTİ+ Aileleri: Taleplerimizi Meclis’te ifade etmek istiyoruz. Bianet. https://bianet.org/haber/lgbti-aileleri-taleplerimizi-meclis-te-ifade-etmek-istiyoruz-269265

Türk Dil Kurumu. (n.d.a). İbne. In Güncel Türkçe sözlük. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://sozluk.gov.tr/?ara=ibne

Türk Dil Kurumu. (n.d.b). Oğlan. In Güncel Türkçe sözlük. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://sozluk.gov.tr/?ara=o%C4%9Flan

Tymoczko, M. (2010). The space and time of activist translation. In M. Tymoczko (Ed.), Translation, resistance, activism (pp. 227–254). University of Massachusetts Press.

Tymoczko, M. (2014). Enlarging translation, empowering translators. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315759494

Yardımcı, S., & Güçlü, Ö. (2013). Giriş: Queer tahayyül. In S. Yardımcı & Ö. Güçlü (Eds.), Queer tahayyül (pp. 17–25). Sel.

Walters, P. (Executive Producer). (2022–2024). Heartstopper [TV series]. Netflix.

Zanettin, F. (2018). Translating comics and graphic novels. In S.-A. Harding & O. Carbonell Cortés (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and culture (pp. 445–460). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315670898-25

Zanettin, F. (2020). Comics, manga and graphic novels. In M. Baker & G. Saldanha (Eds.), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (3rd ed., pp. 75–79). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315678627-17

_____________________________

1 All (back) translations in this article are by the author unless otherwise indicated.

2 Officially founded in 2005, Kaos GL Association is the first LGBTQI+ civil society organization in Turkey. The group has been actively working since 1994 on the publication of the journal, Kaos GL Dergi, and of brochures, reports, and books. It has also been involved in organizing conferences and meetings to promote human rights, to campaign against discrimination and to provide visibility for LGBTI+ people in Turkey (Kaos GL, n.d., para. 20).

3 “Velev ki”, which originates from Arabic, is a subordinating conjunction in Turkish that is frequently used by President R. T. Erdoğan.